Contributed by Yannick Deza, publisher of Data Bites.

I have long been a fan of DFS Lab, the “research-driven venture capital in Africa”.

It’s the only VC firm on the continent that consistently shares – publicly and transparently – nuanced, long-form reflections around its investment thesis.

By doing that, they gifted the ecosystem not just with high-quality articles, but new terms/concepts to describe & make sense of tech in Africa.

Kudos to them! 💥

In a world defined by information overload and sensationalism, mental clarity is one of the most underrated qualities we should consciously strive to cultivate.

How do you know what you know? What is the deep meaning of it? If you cut through the noise, what do you see?

Trying to answer these questions – peeling all the layers of opaqueness – most people would find themselves naked.

This is why, drawing inspiration from the Almanack of Naval Ravikant, I am happy to propose – for the first time – the Almanack of DFS Lab: 6 theoretical primitives to make sense of VC investing in Africa.

These are six concepts coined by the firm that I find extremely insightful/useful in my activities as a researcher/investor:

- The Frontier Blindspot

- Fortune at the middle of the pyramid

- The B-side of African Tech

- Cyborgs vs Androids

- Invested infrastructure

- African S-curves

The original articles are all available on the DFS Lab website and Medium page.

My contribution mainly consists of summarizing my understanding of them & complementing them with my own ideas.

Lessgò.

Subscribe

1) The Frontier Blindspot 👀

Premise: The world has developed “intuitions about how technology markets are structured and what successful technology companies look like”. Cool.

However: this learning process took place strictly in the context of Western economies.

Ergo: the same frameworks do not always apply to frontier markets (like Africa).

Thesis: the disconnect between how we think tech is supposed to work versus how it really works – in Africa & other frontier markets – is the Frontier Blindspot! 💥

It is a blindspot because we are partially clueless – how tech markets work or don’t work in Africa has yet to be demonstrated. As we cannot copy-paste, learning happens by trial and error, thorough research, and on-the-ground experience.

What type of bias did we borrow from the Global North when making our assumptions about tech in Africa?

- we overestimated the pace of digitalization;

- we underestimated the strength of informal markets;

- we overlooked the state of infrastructure and consumer purchasing power

When you factor in low-paced digitalization, strong informal markets, and quirky infra, you’ll see that a lot of common startup wisdom about business models, distribution strategies, and growth projections, won’t apply to the continent.

However, local entrepreneurs are still finding unique ways to apply the “modern startup stack” to the specifics of the African environment.

This is where the real opportunities are, and the areas of excitement include:

- Physical logistics

- SME solution stack

- Financial building blocks

- Agent networks

Although these things may seem obvious today, I think they are still not obvious to many, and they certainly were not obvious in 2020 (when the article came out).

What I find particularly useful about this piece is stressing the differences in infrastructure and purchasing power. When looking at pitch decks, I try stress the following questions:

- what needs to be there for your product to be made, consumed, or delivered? (read: infrastructure)

- How many people can buy your product, regularly? How do you know it?

We are about to have a taste of it with the next concept ✨

2) Fortune at the middle of the pyramid 🔺

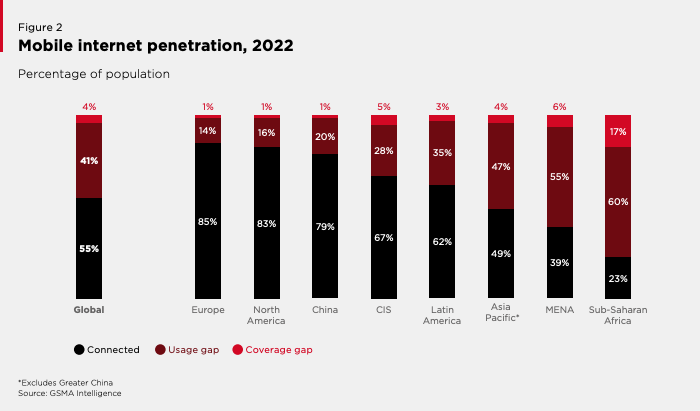

Who is the African consumer & what is the real size of the African market for digital products?

Hashtag: debunking the (once) popular tag “Nigeria is a market of 200M people” with some rigorous thinking.

Why?

Because population size does not equal market size, we cannot boast “the youngest population in the world” without looking at income brackets too.

Let’s proceed in order.

- “Most B2C tech startups are seeking to make money from people’s discretionary spending”

- Discretionary spending is the spending power that remains once covered for necessities like food, clothing, and shelter.

The question asked is: among the 200M fellow Nigerians, how many have the discretionary spending for my type of product?

In the image below, we can look at income levels and their percentage of discretionary income (in Africa).

If you are a B2C startup, what is the juiciest segment?

As a fairly coherent group, the people earning between $5-$10 – while comprising only ~10% of the population – have one of the highest discretionary spending power combined.

This is the fortune at the middle of the pyramid: the segment having enough people, with enough discretionary spending power. To the left of the curve, there are a lot of people but with little money; to the right, they have a lot of money but they are too few.

Now, speaking of unit economics: how much does it cost to acquire these customers? Here things get trickier.

In Africa, higher incomes are usually digitally-fluent city dwellers. Their geographical concentration, professional status, and greater online life, make them perfect targets for digital acquisition strategies. The same doesn’t necessarily hold for lower-income prospects: acquiring them is harder and costs more (with traditional digital methods).

To this comes a paradox: if the cost of acquiring a new customer is way more than what you earn from them, you will soon move to serve higher-income consumers. However, if you only serve the +10$ income bracket, at some point, growth will stall and you’ll need to move cross-border (not easy).

What can we learn from all we just stayed?

- purely consumer-focused apps that do not focus on necessities (read: targeting discretionary spending) face unique challenges with monetization in Africa. This is because

- the largest economic opportunity sits within the 5-10$ bracket, but the cost of acquiring them is high due to lower digital presence.

Moving forward, I think two very important corollaries emerge about “how to be successful”:

- build apps focused on necessities, or focused on the business equivalent of “necessities” (restocking, working capital, inventory etc..);

- if you target consumers’ discretionary spending, invest in human agent networks, the physical point of entry to most digital experiences for middle-of-the-pyramid Africans.

Offline agent networks play a vital role in African tech, and there are plenty of examples.

Personally, whenever I look at the pitch deck of a B2C company:

- if they target offline acquisition, it means they are serving the middle of the pyramid;

- if they don’t mention offline acquisition, it means they are serving the top of the pyramid.

Hence, I’ll start to wonder. Given the risk and the complexities of moving cross-border, can they make money (read: positive operating profit) before moving cross-border?

Enjoying the article so far? Share it with bruvs and siss 💥

3)The B-Side of African Tech 🍑

This article draws inspiration from Wang Huiwen, the co-founder of Meituan Dianping, the most successful Chinese food delivery company, turned super-app.

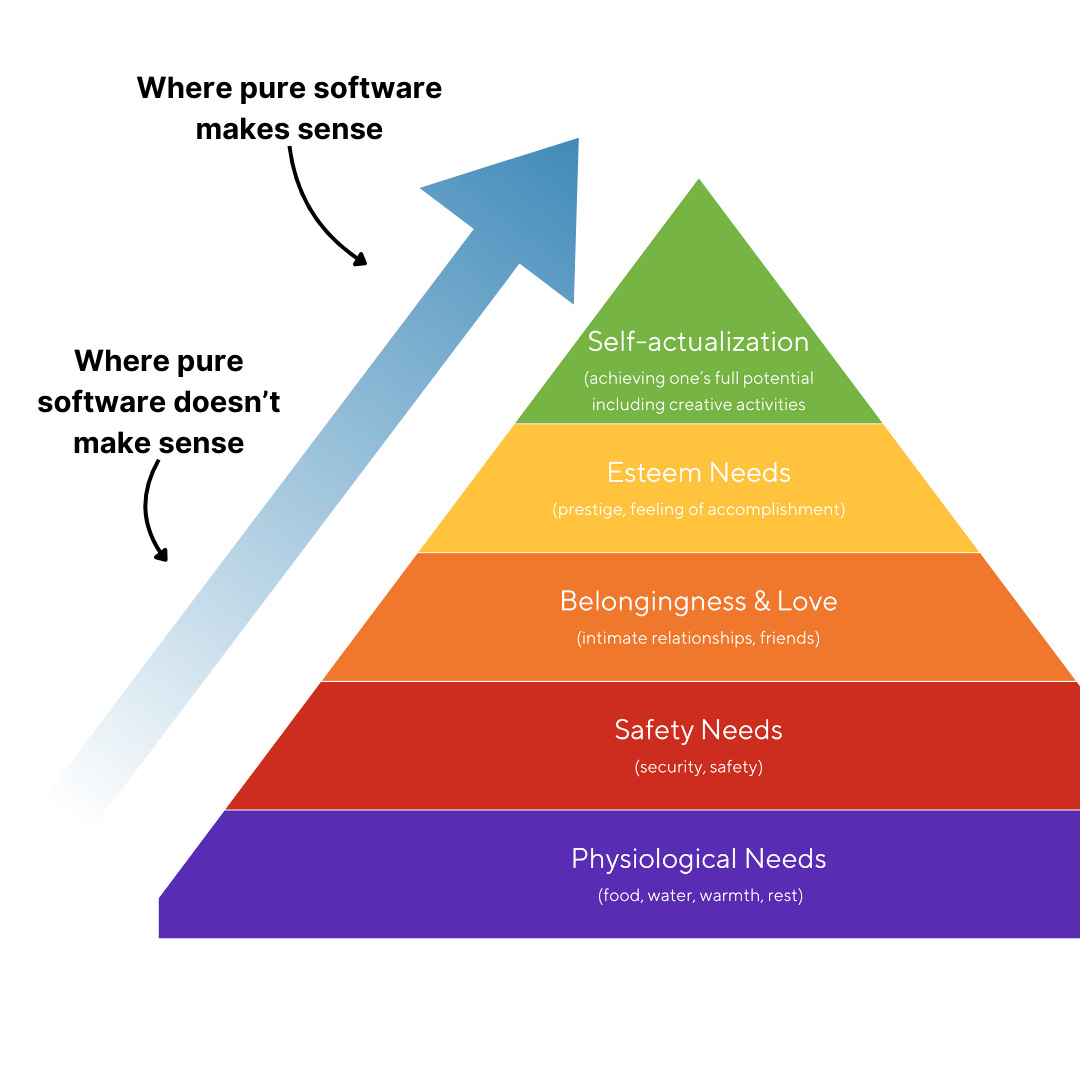

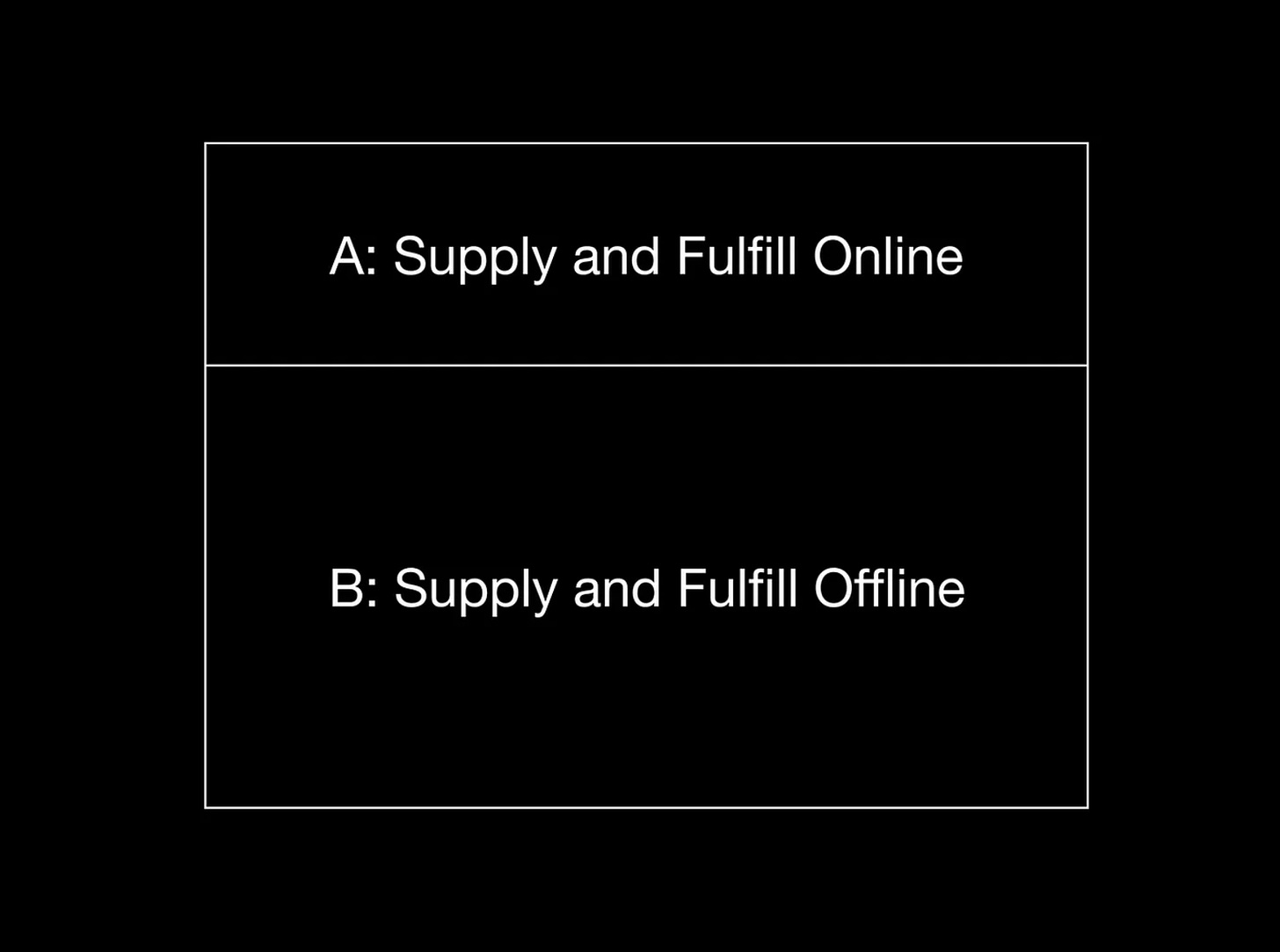

In an issue of the newsletter “The China Playbook”, Huiwen defines the internet industry as made of two sides:

A-side: Supply and Fulfill Online

B-Side: Supply and Fulfill Offline

Side-A is products and services that are “pure internet”, as they can be delivered and consumed entirely online. SaaS (Salesforce), video-games (Voodoo), streaming (Spotify), etc…

Side-B is products and services that are delivered offline and consumed offline. Think of retail (Amazon), mobility (Uber), ticketing (Ticketmaster), etc…

If we have to apply this distinction to African economies, we would see that side-A (online utility) is smaller, compared to side B (offline utility).

The reason is that “fully digital experiences are either inaccessible, unaffordable or don’t cover the primary consumption needs for those in the bottom 95%.”

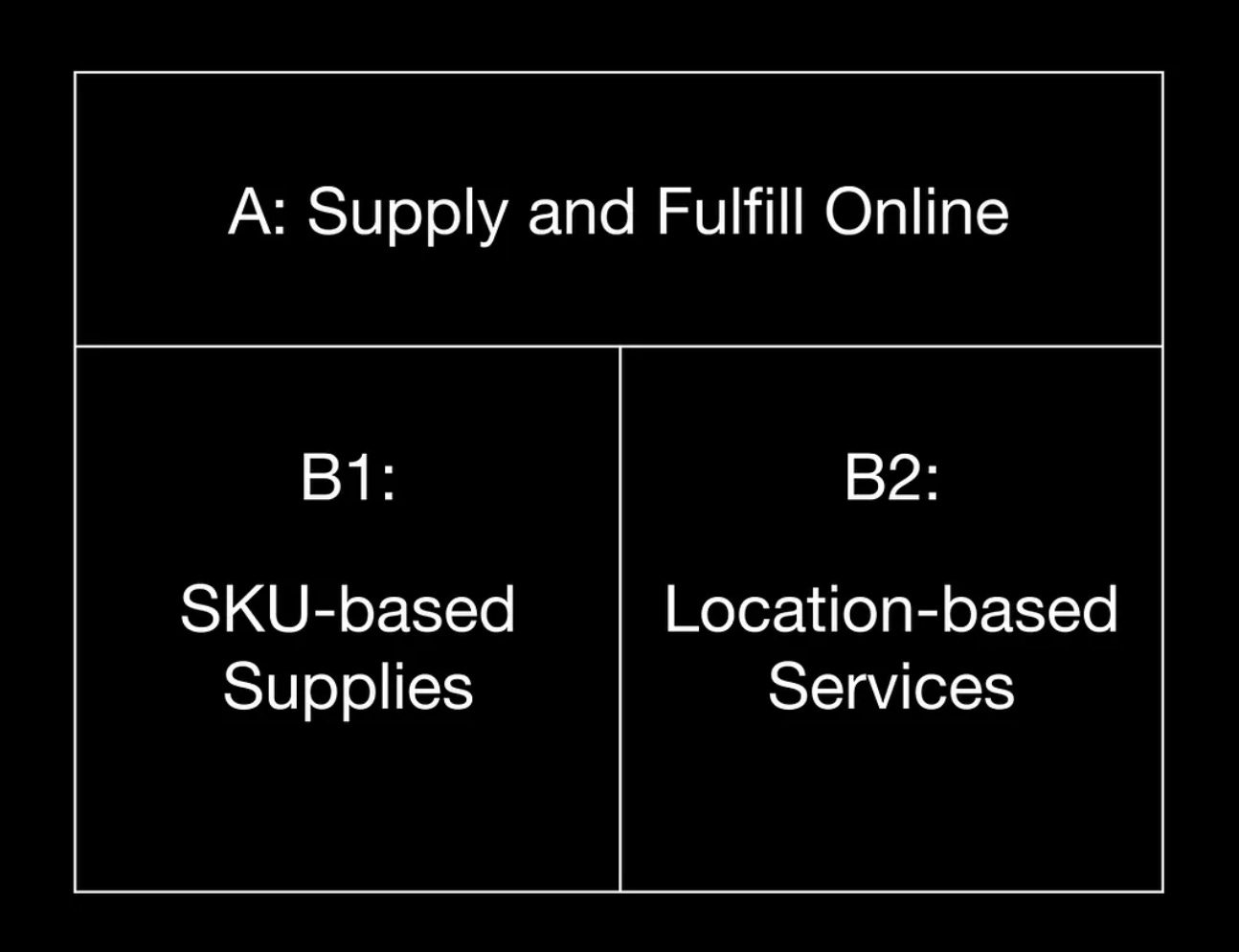

Ok cool. Let’s have a closer look at the B-side then. The B-side can be further divided into two sub-sections:

B1: SKU-based supplies

B2: location-based services

B1 is companies like Wasoko, Omniretail, and other traditional marketplaces. As digital businesses positioning in between the sourcing & delivery of physical products, their core competencies lie in ”understanding SKUs (stock keeping unit), understanding the supply chain, and understanding pricing”.

B2 is companies like Hubtel and Wahu Mobility. They are location-centric, as the physical location of customers & partners is a key element of their value proposition. For example, a ride-hailing company like Uber will need to recruit drivers in your city and ensure there are enough in your area as you order a ride – otherwise, you won’t be able to access their service. B2 businesses demand a larger offline team to manage operations closer to the customers.

What learnings do we have here?

B1 leverages technology to “improve the efficiency of existing value flows and reorganize pricing power”. On the contrary, “B2 is physical ubiquity”.

Let’s stop here.

In the article, Stephen Deng (DFS Lab MP) expands on the original concept expressed by Meituan Dianping founder.

When Wang Huiwen talks about B2 “location-based businesses”, he is primarily referring to ride-hailing, bike-sharing, and food-delivery, products made accessible by smartphone proliferation, which unlocked & democratized location data. These businesses are useful because you can see your location with your phone, and other people can see it too.

Deng however, twists its meaning for the African context, attaching to it the familiar notion of physical ubiquity: B2 businesses are interesting because of their physical proximity to the customers, mobilizing people and resources last-mile. Other than delivery, one can think of mobile money agents and social commerce as a form of B2 businesses. Their utility comes from their ability to integrate kiosks and people from your neighborhood in their business model. They are relatable, they are next door.

In short, they are more similar to Cyborgs, instead of Androids. What?

You read correctly. The concept of “B-Side of African Tech” is strictly intertwined with that of “Androids vs Cyborgs”, that we explore in the next section (before wrapping up with my two cents on this stuff).

4) Andorids vs Cyborgs 🤖

Androids: solutions that replace informal markets with digital, formalized parts and processes

Cyborgs: solutions that enhance informal markets by arming them with digital, formalized parts and processes

Androids use tech to replace a set of existing actors.

Cyborgs use tech to improve the work of a set of existing actors.

Stephen Deng claims that we cannot brute force androids into existence if we are incapable of replacing informal players with significantly better solutions. And if we can’t replace them, we’d better empower them by building cyborgs.

It might seem like a B2C (Android) vs B2B (Cyborgs) play, but it’s more nuanced than that. Examples?

The ultimate Android example is Jumia and all Amazon-inspired B2C marketplaces: “replacing the local market with an online option that is meant to be more convenient, have more options, and is fully digitized”.

However, I think the same holds for many agri-tech platforms (like Complete Farmer or Winich Farms) that aggregate farmers’ produce and facilitate access to market & agro-inputs. In almost every pitch deck you will read about them “cutting out the middlemen”, the set of informal buyers and sellers who move crops to markets, whose commissions eat out farmers’ margins and drive inefficiencies (btw these platforms raised a lot of funds, but it’s not clear to me how much money they are making).

Cyborgs, on the contrary, look like tools that empower small businesses, applying a mix of online and offline. Instead of replacing existing relationships, they “supercharge them with digital optionality when the need arises”.

Both B2-side businesses and Cyborgs, tell the same story: existing structures can be valuable when they are empowered, instead of substituted.

Ok, but empowered how?

In my opinion, an online-offline Cyborg approach, can only be one of two things:

- cost-effective offline distribution and/or marketing – agents knocking on doors or setting up shops;

- tech-enabled intermediaries/retailers – empowered by a digital backend or specialized hardware.

That’s it!

Moniepoint is Africa’s fastest-growing fintech. Its distribution model? An army of human agents armed with PoS devices, knocking on merchants’ doors. The company revolutionized the capacity for Nigerian businesses to collect digital payments.

→ a Cyborg approach to digital payments.

Retailers’ bookkeeping apps like Oze and supply-chain management tools like Jetstream, both started as digital super-charger of African businesses: I give you tools to better manage invoices and logistics. Fast forward a couple of years, and they both ended up embedding credit and solving the pain of access to capital.

→ a Cyborg approach to digital lending.

I think Cyborg either means giving more “legs and arms” for asset-light digital businesses, or making “legs and arms” (SMBs) more competitive with digital tools.

Digital solution → leave a digital trace → data + learning models → better decision making

Digital solution → relational database & data integration → operational efficiencies

Digital solution → composable software stack → APIs & integrations → new products/services delivered on top of the main product

🪄🪄🪄

More in general, I think that both the “B-Side” and “Android vs Cyborg” arguments tend to over-emphasize the promises of the physical ubiquitous approach, without addressing the elephant in the room: we need more hardware.

A lot of things can be done with your phone, but not everything can be done with your phone, and sometimes, a phone is too much.

Limited storage/memory, weak bandwidth, and high data costs still represent hard limits to app utility for the average African business operator. A phone can do a lot, but not everything.

Safiri is a Tanzanian company equipping bus companies with thermal printers, and customers with digital ticket purchase options. They record transactions “digitally”, and print tickets “physically”. A good blend of digital and physical coming together. No need for Industry 4.0 here, just basic hardware tools.

And yet, I am not seeing enough investors stressing how specialized hardware – as well as consumer hardware – can play its role in the tech landscape.

We need more hardware. We can’t expect to revolutionize the continent simply with apps running on cheap smartphones.

I feel we’ll see major shifts when large-scale hardware manufacturing that truly responds to local business needs comes to fruition.

And yes, somehow, I am still convinced this can be a VC play.

Enjoying the article so far? Subscribe to Data Bites & have more of this 💩Subscribe

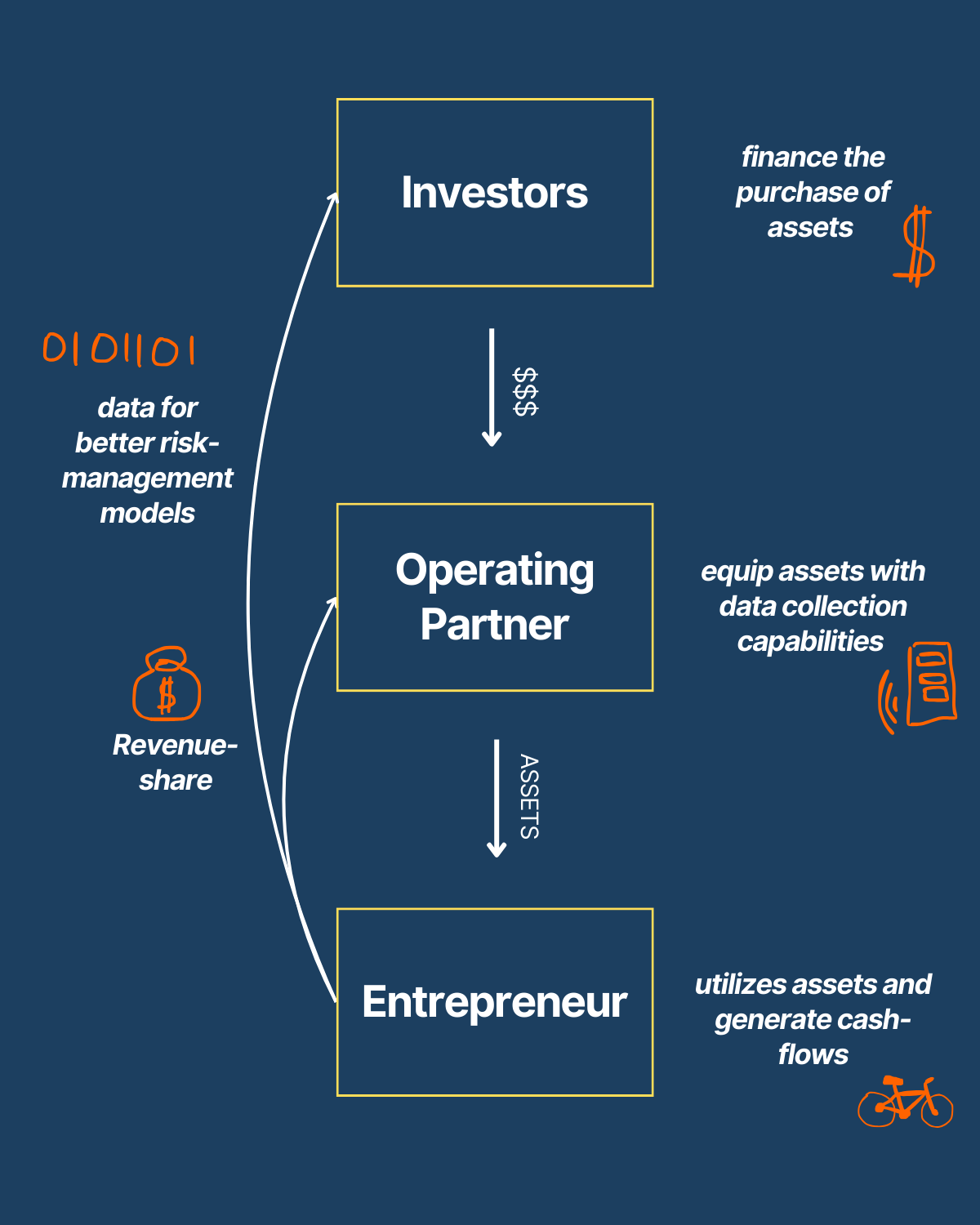

5) Invested Infrastructure 🏗️

The concept is simple, yet powerful: the infrastructure built in the past has a lasting, indelible influence on our present & future.

Economists call it “path dependency”: society builds on top of what has been built, and this process makes us drift toward a trajectory of development and away from others.

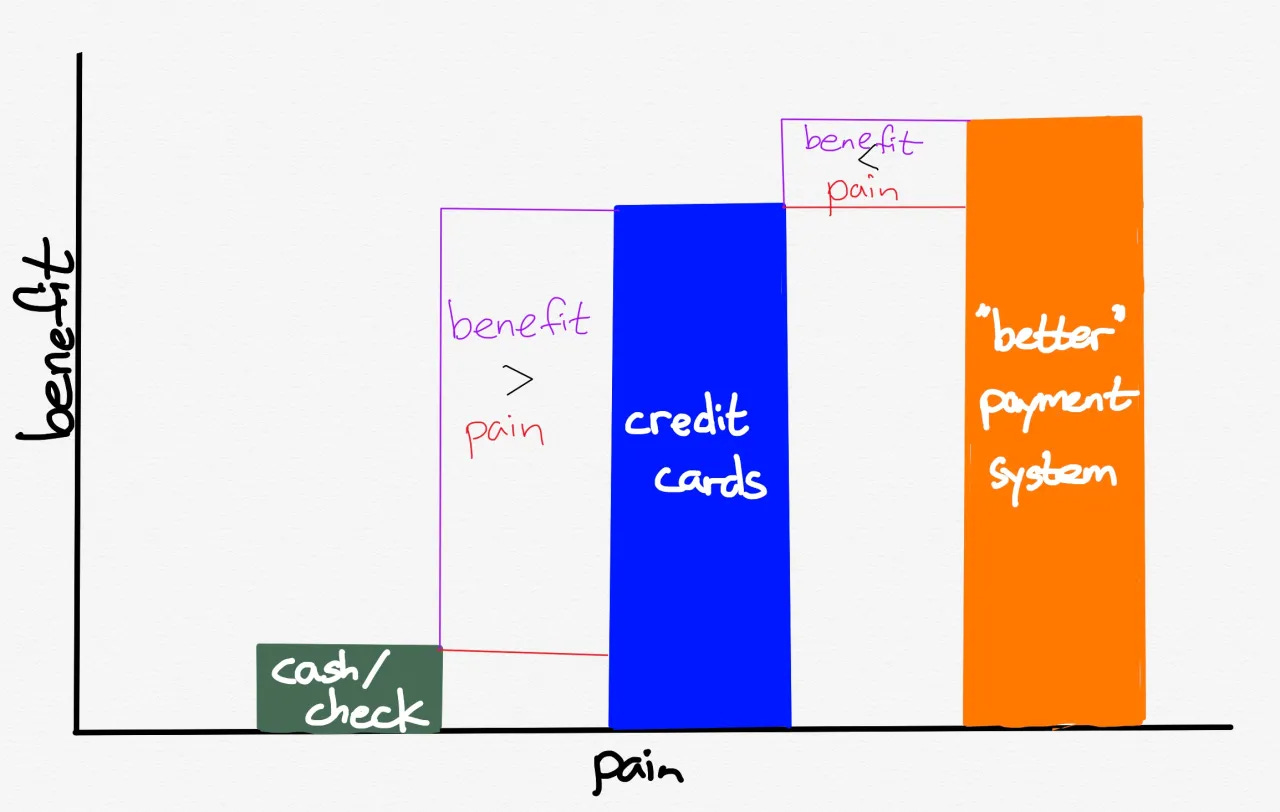

In the United States, payment infrastructure has been built “for a time when phones were not as ubiquitous and hard-wired ethernet was increasingly common.”

The proliferation of PoS devices & phone cables (& later fiber cables), gradually made up the physical network on top of which credit cards’ adoption became widespread.

The alternative to cash travels on rails that took a long time to build, but once in place, it is hard to replace. It’s the hidden cost of path dependency: the more we build on top of invested infrastructure, the higher the switching costs to a different system.

“They have since gained ubiquity, and because mobile phone-based services can only offer marginal improvements, the system stays resilient — it is challenging to overcome the inertia of this invested infrastructure”

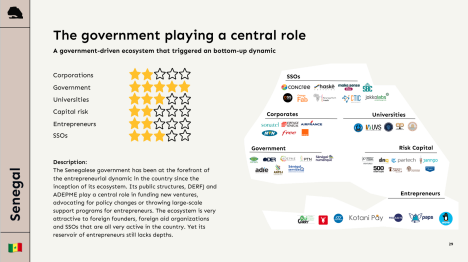

What is the invested infrastructure in Africa and how will it impact its future?

It is an important question to ask because – as we have seen – companies that leverage invested infrastructure can have a competitive edge, reducing costs and frictions to adoption; those that try to replace it might sink under the weight of high switching costs & behavioral change (although in some cases – boom jackpot 🎰).

If we think of financial infrastructure, in Africa the equivalent of the US card network is a combination of:

- a human agent network

- phones & SIM cards

- tower cells

It hasn’t always been the case. The capillary presence established by telco companies in the continent from the 90s onward, brought along the way important infrastructural development that served as the launchpad to mobile money: financial infrastructure borrowed from the already existing communication infrastructure.

A human agent network could now be used to on-ramp/off-ramp physical cash.

Phones and SIM cards became wallets.

Tower cells relayed information – and now value – across long distances.

Innovation on top of invested infrastructure.

But it’s not over.

As the new payments infrastructure emerged, further developments “up the ladder” could see the light of day: “The combination of USSD-based mobile accounts that worked on every phone and cash-in/cash-out agents in nearly every neighborhood and village proved to be powerful infrastructure on which to build new product offerings”.

The first wave of successful tech businesses on the continent – real “market-creating” innovations – are the product of it.

Examples:

- First generation: pay-as-you-go solar (like M-Kopa)

- Second generation: digital lending

Access to energy & access to credit. Both are built on top of mobile money infrastructure, built on top of telco’s invested infrastructure.

What lessons can we take home from this chapter?

- invested infrastructure matters

- it looks different in Africa than in other places

- opportunities exist for those who build on top of it + those who make it more efficient

Personally, I find myself asking the question” What’s the invested infrastructure here?”. And not just for payments, but for commerce, logistics, agriculture etc.. In short, it translates to: how things are done now, how much does it cost to switch and who has interest in doing it?

6) African S-Curves ⚡️

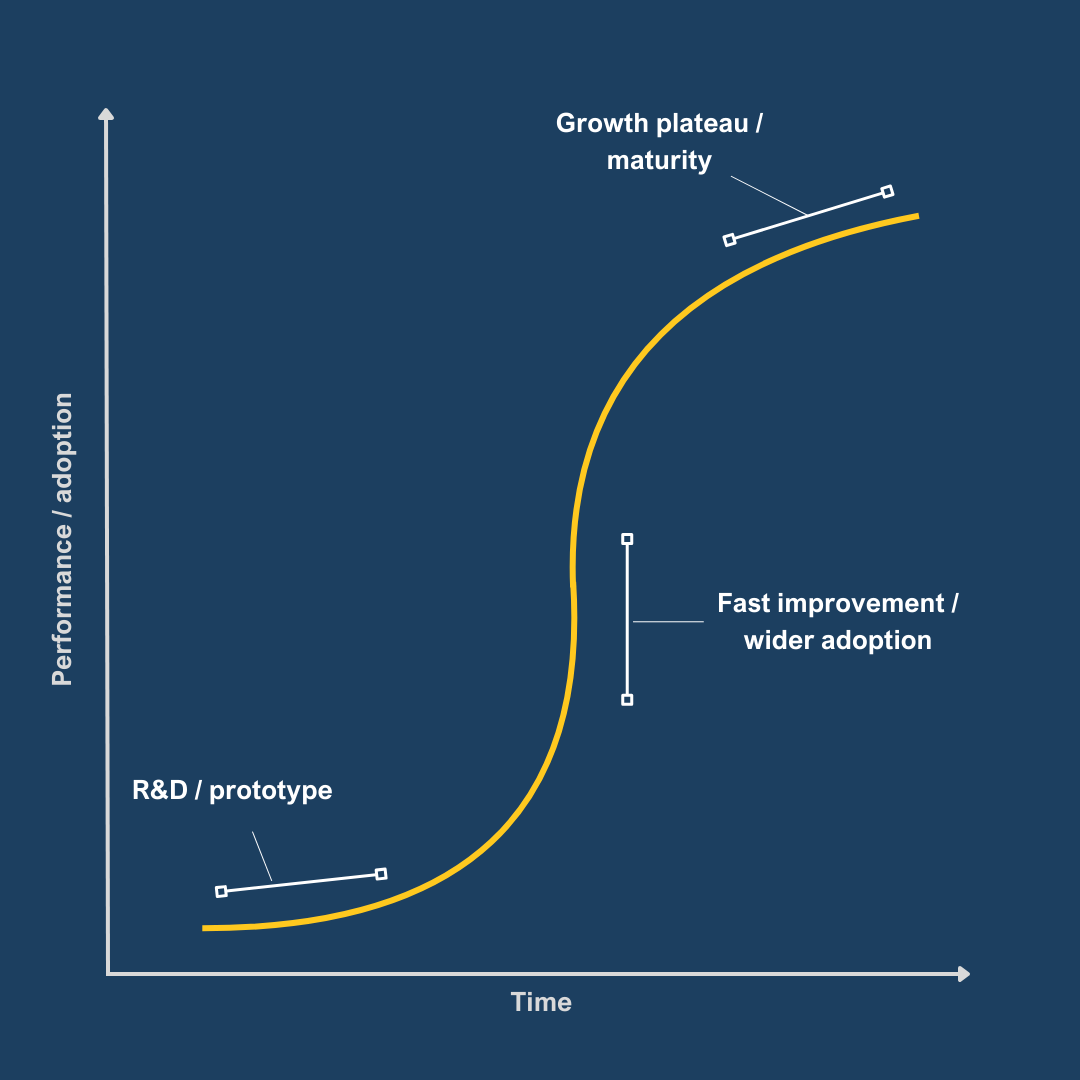

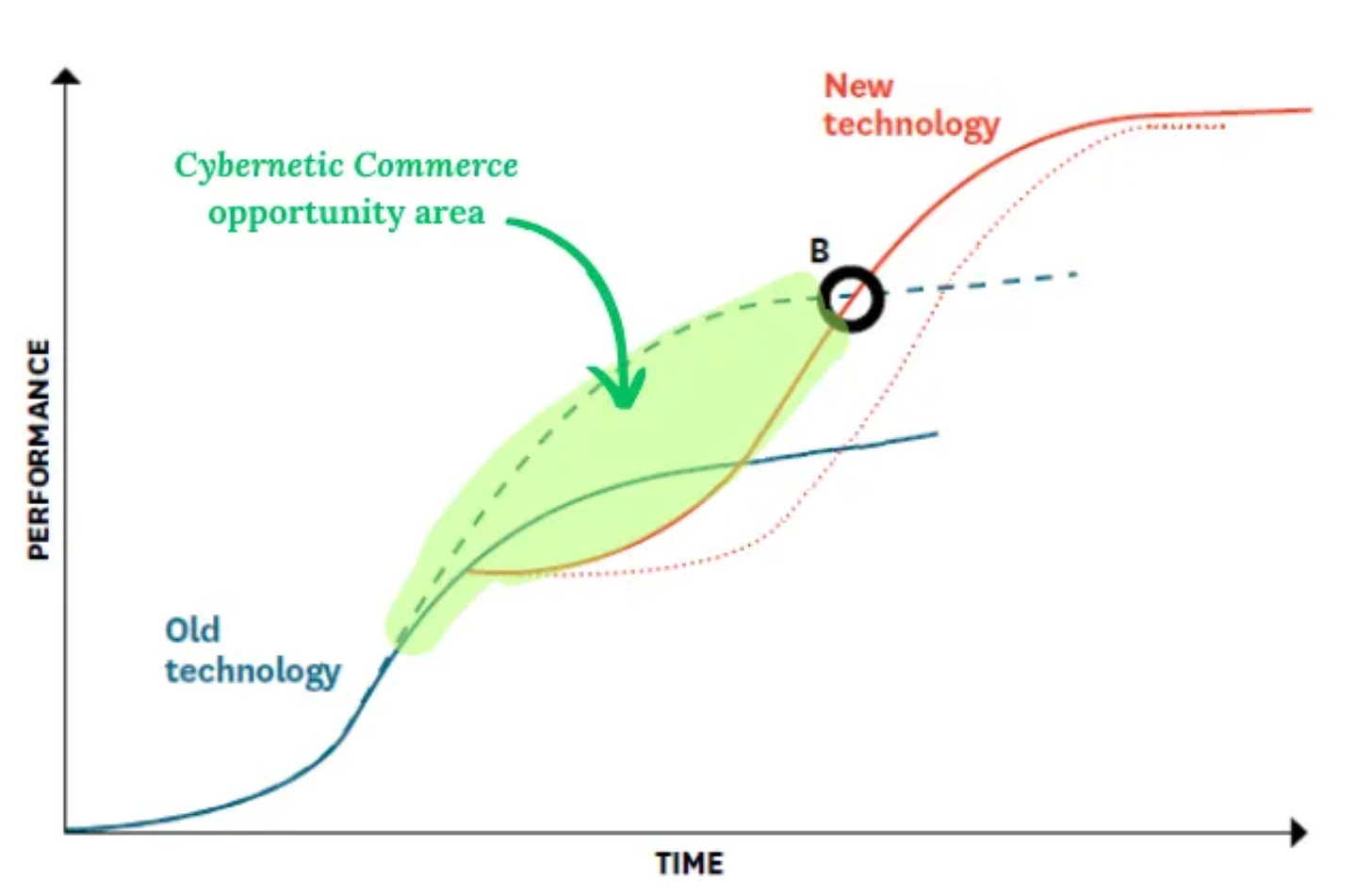

S-curves describe the performance of a new technology – or a technological toolset – over time.

In the beginning, during the R&D and prototyping phase, adoption is minimal and the potential of tech still needs to be validated. The curve is flat and growing slowly. Think of electric cars 15 years ago. It is the territory of university budgets, public finance, and research grants.

When the tech starts showing signs of improvement, it is followed by a steep acceleration in performance and increased adoption. Think of Generative AI one year ago. It is the land of VCs, profiting “by investing in emerging tech before it’s mainstream and exiting when growth plateaus”.

Finally, when a technology is mature, adoption widespread and there is little room for marginal improvements: the tail of the curve flattens. It is the PE and stock market game.

And then, onto the next technology, that will replace the incumbent with the next S-curve. Venture capital funding follows the S-curves cycle, the peak funding being when the curve is at its highest steep.

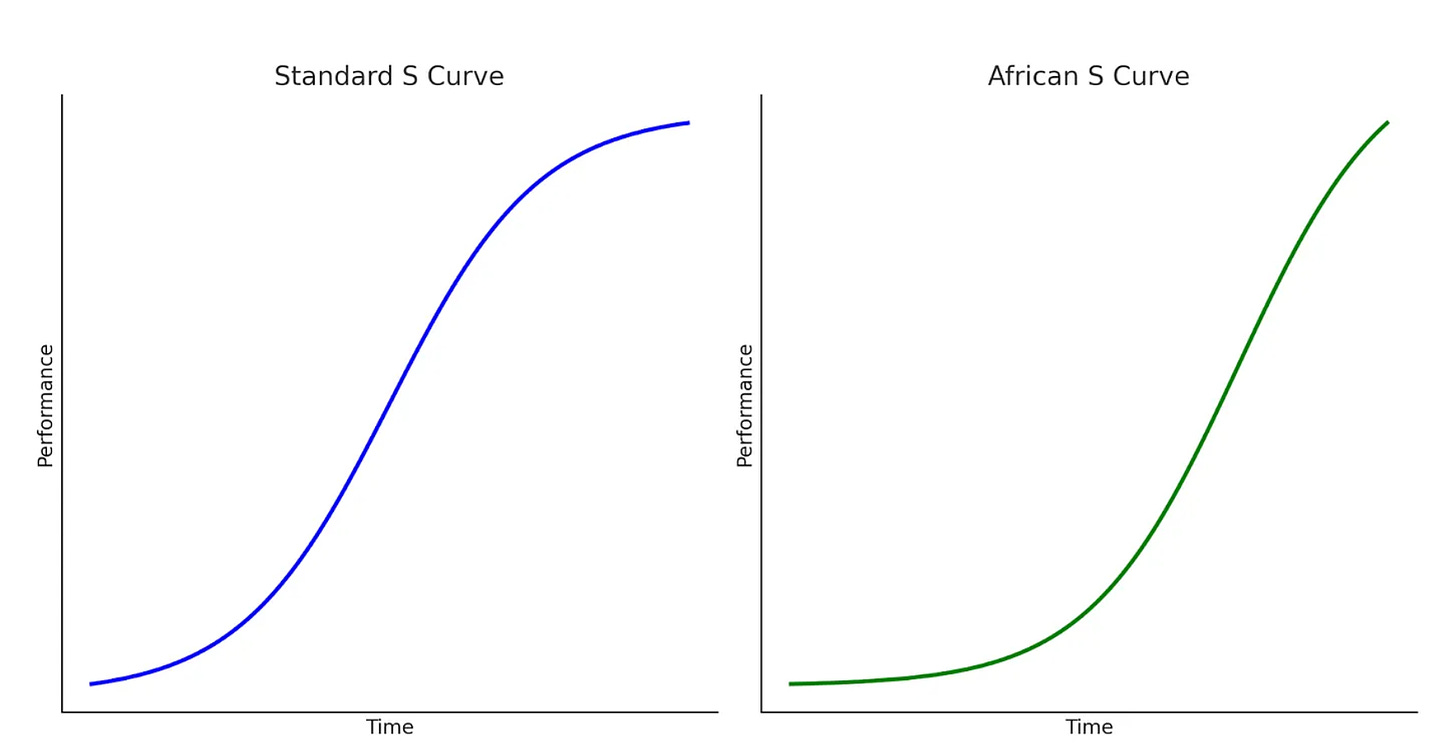

Now: in the wake of funding drought, startup bankruptcies, and crowding away of international investors, what can we say about the shape of the African S-curve?

One: African S curves have much longer tails.

This means that it takes more time for tech in Africa to see widespread adoption. Rather than a limit to technology performance, the problem lies in the lack of market readiness.

Read: “Customers don’t need new tech, or don’t trust new tech, or can’t afford new tech, or don’t have access to infrastructure for new tech, or don’t believe new tech provides enough value vs. old tech”

Two: African S curves have much steeper slopes

On the contrary, once adoption kicks in, the potential for improvements in technology can last for a very long time, going beyond what was once imagined.

The acceleration phase lasts a long time along with its benefits.

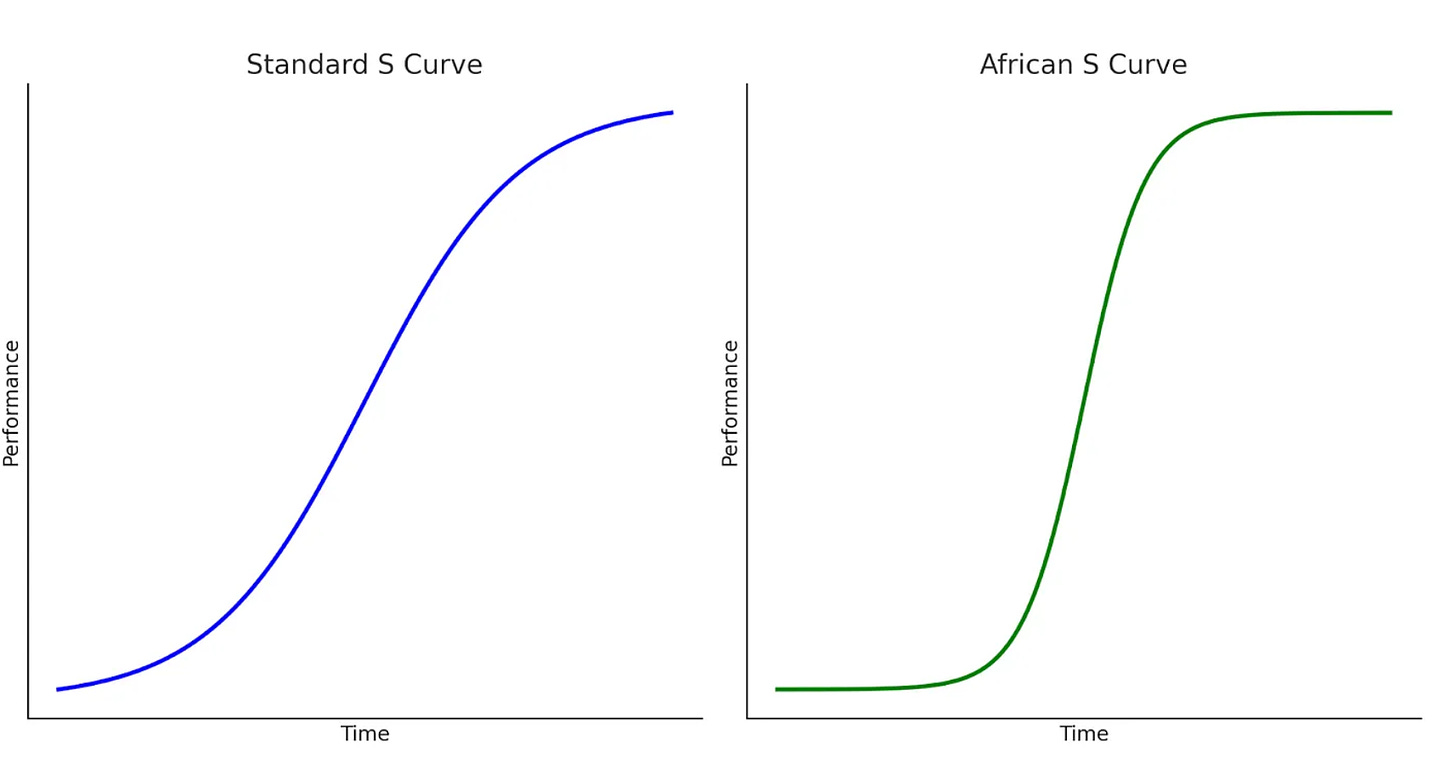

How do we change from one S-curve to the other? When will the new tech replace the old one?

There are 4 different scenarios.

If the old tech is not improving, and the market is ready for a novel solutions, then we’ll have a quick transition. This means heading towards Point A, and what people cheer as Africa’s technology leapfrog.

On the opposite side, if incumbents are delivering increasingly better utility to consumers, who are not ready to change for newcomers, then we’ll have a very gradual and slow transition. Ergo, heading towards Point D.

Many people either bought the point A narrative (technology leapfrog), or buys into point C one. They think old tech is crap, inefficient, and not making any progress. However, the market is not ready for new digital solutions yet. It’s a matter of time.

Stephen Deng, on the contrary, thinks we are heading towards point B. A situation where yes, the market is not ready, but the old tech – and the ecosystem around it – is still improving.

Think of mobile money. It is a fairly old technology ( and USSD codes), but it can still deliver innovation to its users. Telcos are blending digital offerings into their core model; traditional financial services are integrating with the mobile money ecosystem for seamless interactions; new products are developed on top of it every month.

If MoMo is the old tech, the new tech would be close to neo-banks like Djamo. How many customers does one have vs the other?

The shelf life of telecommunications technology has been pretty long. No surprise than that the true champions of tech in the continent are telcos. Companies like MTN, Airtel, Safaricom. This is in stark contrast with the Google, the Meta and the Microsoft of North America.

The main argument is the following: from now on, until we reach point B, a lot of incremental innovations will be built around the existing tech. We need to surf it 🏄🏽♂️

It is what Deng calls the “cybernetic commerce” area, yet another version of the Cyborg thesis.

The most interesting element of this article, to me, is the mental framework that comes with it: how many incremental innovations can still be built on top of the existing rails?

When you look at African markets overall, you’ll see that a lot of problems can be solved with existing technologies. There is no need for a breakthrough.

How to deliver the benefits of tech without losing money: this is the number one skill a founder must have.

This is the end, my friends. I hope you enjoyed the read. Writing this piece I’ve noticed that – as telcos in Africa – my essays have room for improvement. In particular, from now on I will try to deliver:

- more real-life examples (what companies, what products etc…) → it helps with mental clarity when you have more than 1/2 examples

- more exit simulations (revenues, potential returns) → VC exists where outsized returns exist, and we need to be more rigorous on that.

Onto the next one! 🚀 🚀 🚀