Contributed by Carine Vavasseur, CEO of Ignite.E via Realistic Optimist.

A growth path

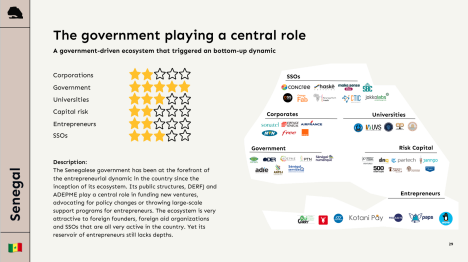

Considered a model of democratic stability in turbulent West Africa, Senegal has recently witnessed the emergence of its own startup ecosystem. Ambitious economic growth objectives, crystalized by the 2012 “Senegal Emergent” plan, led to digital infrastructure improvements, legislative reforms, and collaborations with foreign savoir-faire (StartupBootcamp Afritech, AfricArena, Open Startup Tunisia, La Startup Station, Draper University…).

Following continuous efforts by the Senegalese private sector, the past 5 years have seen the Senegalese government become a driving force behind the ecosystem’s development. This is unlike some of its neighbors such as the Ivory Coast, where the ecosystem evolved more organically. Those governmental efforts are encapsulated in the creation of dedicated agencies such as La Der, where I previously worked, as well as previous existing agencies like ADEPME.

While still young, the ecosystem’s flourishing is concrete. Local champions such as Paps and Chargel have raised significant rounds and are scaling fast. Others like Logidoo, Taaral, or Compact are on their way to significant impact.

Seminal fintech startup Wave, American-funded but African-nurtured and raised, has chosen Senegal as its initial market.

As the ecosystem seeks to elevate and attract foreign investment, deciphering a couple of its specificities is useful.

How VCs should approach Senegal

VCs won’t drastically modify their approach just to invest in Senegal. Not only is the market too small to justify such granularity, but the size of the Senegalese market means any VC investment will have to be pan-African anyway.

That being said, VCs should be cognizant of the different approach to adopt when investing in African startups as a whole. Copy-pasting the investment methodology used for American or European markets is mistaken. Investing in the continent’s startups implies certain subtleties.

The context in which African startups operate is often complex: human/financial resources are rare, and the most pertinent problems to be solved are often at the “bottom of the pyramid”. This implies a tacit impact component, as customers served possess a drastically lower buying power than in California, for example.

When navigating the Senegalese ecosystem, VCs should not hesitate to collaborate. Given the ecosystem’s youth, much of the market data is “declarative” rather than scientifically factual. Trust thus plays a primordial role, and VCs should work together to determine what can be trusted and what can’t.

Since truly VC-backable Senegalese companies are still few, VCs should join forces with the actors propping up and birthing such companies. In Senegal, venture studios such as Haskè Ventures have internalized the creation of promising startups and VCs would lose out by not engaging with them.

A great example is the LionsTech Invest initiative, a local and international investors community and platform that acts as a three-way bridge between investors, startups, and entrepreneur support organizations. Many opportunities and deals happen there.

Foreign vs local investors

Both foreign and local investors have a role to play in the ecosystem.

Local investors are crucial because they have inherent local expertise that founders can benefit from. Additionally, engaging local investors quasi-guarantees that the proceeds from any potential exit will get pumped back into Senegal, in one way or another.

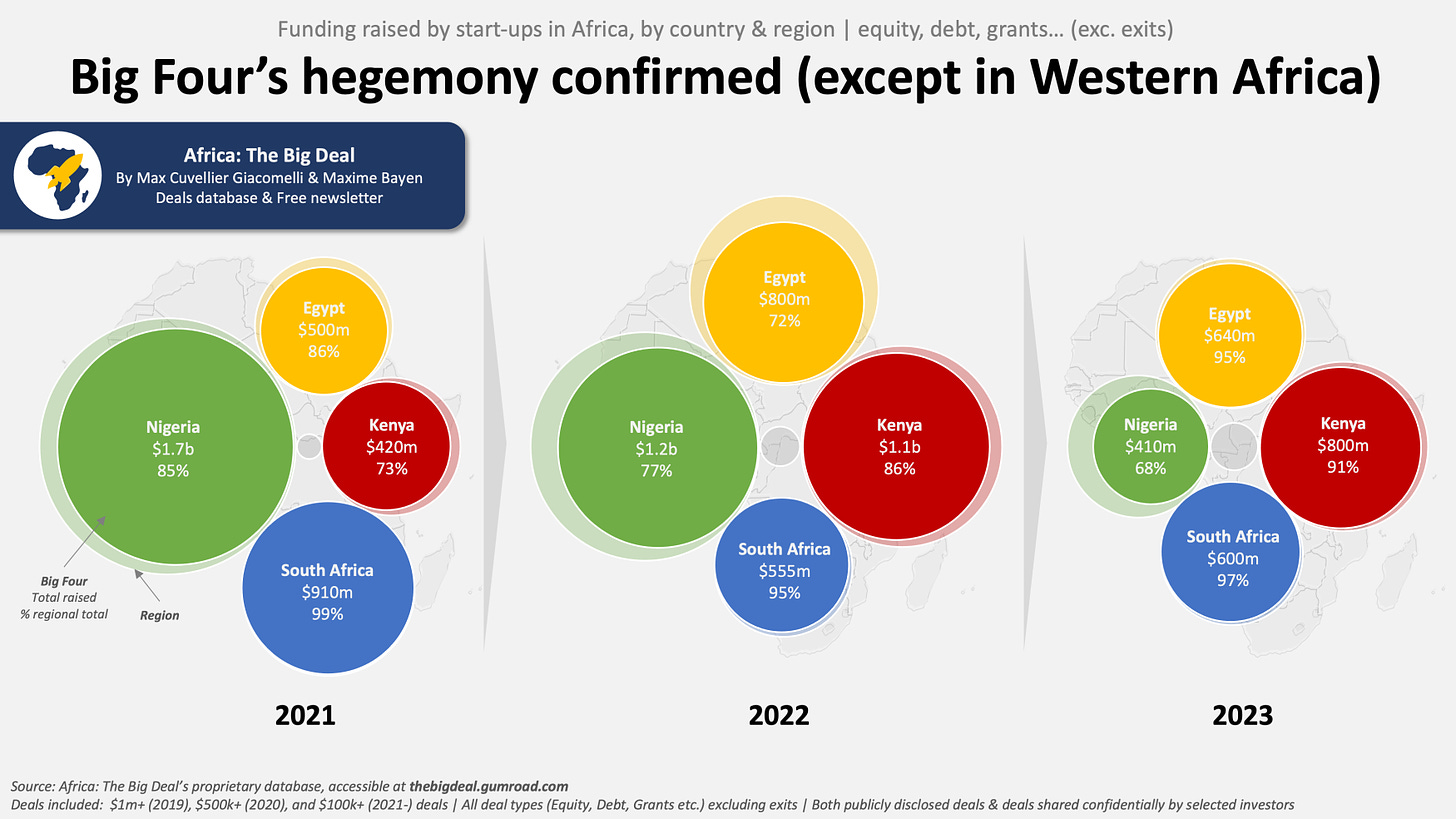

That being said, local investors’ coffers are limited and startups will need to raise internationally if they wish to significantly scale. Data shows that the Senegalese startups that have reached the next level have relied on foreign capital to do so.

Implementing the right legislation and incentives to facilitate foreign investment is therefore paramount to the ecosystem’s future development. This also shows the need for supporting and growing business angel networks, another crucial piece of the puzzle.

A healthy mix of both foreign and local investors constitutes standard best practice for most performant ecosystems around the world.

A political risk?

In what is otherwise considered a model of African democracy, the run-up to Senegal’s upcoming election has been eventful, to say the least. This has worried some of the ecosystem’s partners and financiers. They fear that a radical change in government would hurt an ecosystem that is so-called “government-dependent”.

While the government has played an essential role in the ecosystem’s development, I don’t think dependence is the right word. At its inception, the ecosystem was mainly driven by private actors. At that time, around 8 years ago, I was in CTIC Dakar’s management team, francophone West Africa’s first startup hub established in 2011 on a public-private partnership.

Most of the ecosystem-building efforts were, at that time, led by CTIC and players such as Jokkolabs, the OPTIC (under ICT companies’ patronage), individual IT companies, telcos (mainly Sonatel then Tigo), some private companies mainly through their CSR, international NGOs and aid organizations such as GIZ, as well as a few state agencies.

The government’s strong intervention to bolster Senegal’s entrepreneurship ecosystem commenced 5 years ago with DER’s creation. That governmental intervention has been a success and has decidedly elevated the ecosystem to a new stage of maturity.

That gained maturity is precisely why the ecosystem isn’t government-dependent, as some say. Excellent private initiatives have blossomed, and many learning-filled mistakes have been made along the way. Synergies have been tremendously reinforced and have shown concrete results. Even if there is always a need for more collaborations, some of the main interdependencies that needed to be established now exist. They are to be maintained and strengthened.

The government has played its role as a catalyst for better joint impact by not occupying a monopolistic position and making sure that all the players can come together through various initiatives. This has naturally positioned it as a trusted third party.

The future challenge resides in continuing that positive dynamic, regardless of the new or maintained government in power. The Senegalese state will naturally continue to play a major role, in getting regulation and infrastructure up to speed primarily. It will be the ecosystem’s responsibility to continue nudging it in that ecosystem-building direction.

International aid’s presence

International aid organizations have been omnipresent in Senegal’s ecosystem, just as they have in many other African ecosystems. Their presence requires a deep reflection on how the initiatives they finance remain in the ecosystem’s best interest.

There needs to be a clarification of the financed projects’ nomenclature. Today, many Senegalese incubators have aid money as part of their funding mix. However, this has led to incubators mixing startups and SMEs, the latter more in line with aid organizations’ KPIs. Mixing both can cause serious challenges.

Tech startups and SMEs are structurally different and do not require the same financing, benefit from the same mentors, or hold the same scaling ambition. It would be more effective to create programs tailored uniquely to startups, providing them with startup-relevant guidance.

Doing so will require a diversification of these programs’ funding sources, to include more local actors, private investors, and even founders themselves. Successful founders in particular would be the most apt to craft startup-relevant programs.

To sum it all up, while international aid’s presence has been fundamental, it is time to deeply rethink the programs the ecosystem is building for its startups, in their subject matters, their participants, as well as their sources of financing. Supporting this shift is one of our objectives at Ignite.E.

Conclusion

The Senegalese startup ecosystem has come a long way, carried by exceptional private actors and a voluntarist and increasingly implicated government. Much remains to be done by both parties, and it will be up to the first to hold the second up to account regardless of the election results.

VCs investigating Senegal should first determine an adequate, pan-African investment thesis and participate directly or indirectly in building their pipeline of investable startups. To thrive in Senegal and find the best founders, they shouldn’t hesitate to collaborate and engage extensively with the organizations (venture studios, accelerators) fomenting those rockstar companies.

The ecosystem should rethink what programs are truly useful to Senegalese startup founders, and how various funding sources impact the direction these programs take. More

importantly, each ESO should have a clear and strong vision for itself and the ecosystem, with a plan to achieve it and meaningful KPIs to monitor its impact.

This article was written for and exclusively published in the Realistic Optimist, a paid publication making sense of the recently globalized startup scene.

About the Author

Carine Vavasseur is a leading force behind the Senegalese startup ecosystem. She was an ecosystem builder for La Der, Senegal’s President’s initiative aimed at fostering the country’s entrepreneurship and startup scene.

She is now the CEO of Ignite.E, an ecosystem builder within Haskè group (advisory firm and venture studio) with a mandate to build African startup successes through entrepreneurship support organizations’ empowerment.

She is also a 2023 Mandela Washington Fellow.