Contributed by Mathias Léopoldie, Co-Founder of Julaya via Realistic Optimist.

Optimizing for home runs

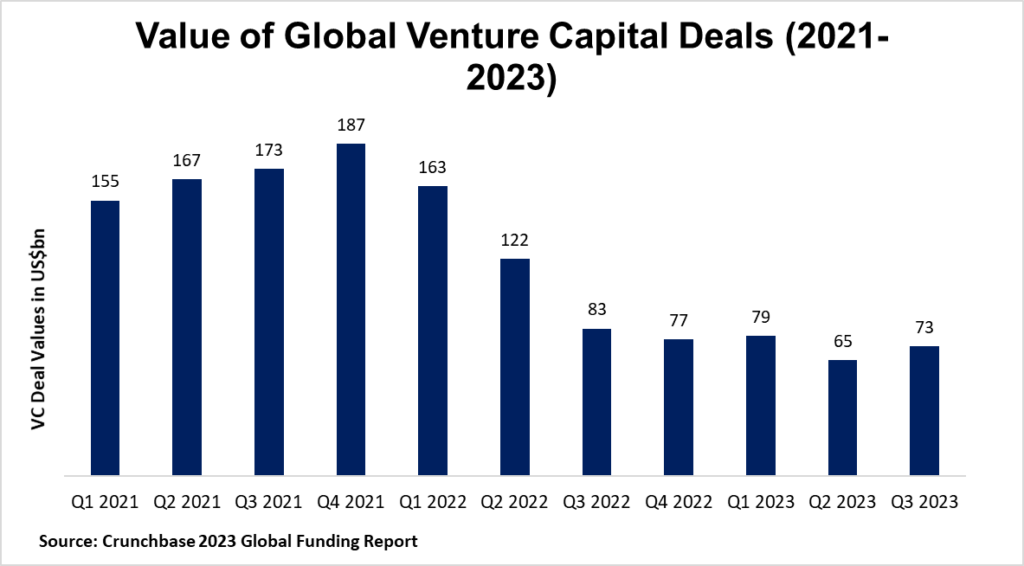

It is said that the first venture capital (VC) firm was founded in 1946, in the USA. The American Research & Development Corporation (ARDC) became famous for its $70,000 investment in Digital Equipment Corporation, a computer manufacturer, which went public in 1967 at a whopping $355M valuation. Investors taking risky bets on companies wasn’t new, but the computer era put venture capital’s singular “power law” on full display.

A baseball game is an apt analogy to conceptualize how venture capital works. The most exciting play, which also brings outsized returns, is when the ball skyrockets over the fence resulting in a home run.

VC is quite similar, as the power law nature implies that a few investments (<5%) will drive most of a fund’s returns. While the number of home runs in baseball might not guarantee winning the season, it does in VC.

This is why VC is an exciting asset class: sharp skill and experience are necessary, but luck plays a non-negligible role. It is no surprise that, amongst asset classes, VC has the highest dispersion of returns. Participants can either win big or lose a lot.

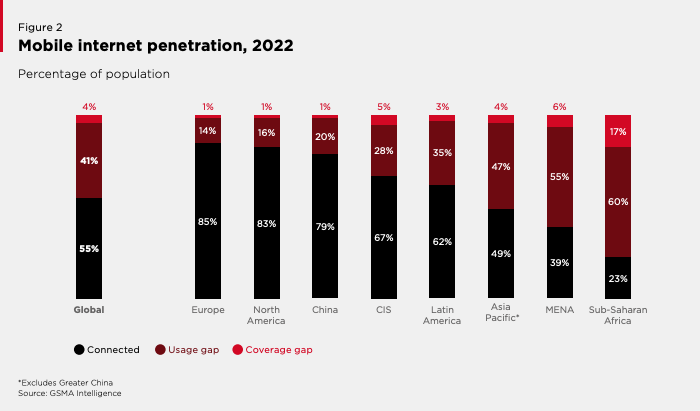

The African VC ecosystem is young, inching past its first decade of existence. The African internet revolution took a different shape than it did elsewhere: between 2005 and 2019, the share of African households possessing a computer went from 4% to 8%, while other developed economies witnessed a 55% to 80% jump over the same period.

One can’t expect a VC industry to suddenly flourish in an economy where microchip-equipped computer and smartphone ownership is so scarce. The heart of the VC industry is called “Silicon Valley” for a reason.

Another trend, however, calls our attention. Namely, the rise of mobile phones on the continent. Currently, over 80% of Africans own a mobile phone, a figure that reaches close to 100% in some countries. The 2000s-2010s feature phone mass production era is to thank. Transsion Holdings, a Chinese public company, tops the leaderboard in terms of mobile phones sold in Africa, through its portfolio of brands (Tecno, Itel, and Infinix).

This offline, ‘computerized’ revolution of sorts is significant for the continent, as a large part of Sub-Saharan Africa’s population still lacks internet access. This includes people who own a feature phone but no smartphone, or people for whom the cost of internet data is prohibitively expensive. Internet’s geographical reach in Africa also remains patchy, further complicating the equation.

Unsurprisingly, telecom operators have emerged as this mobile phone revolution’s winners. The mobile money industry is a striking example: a fertile mix of USSD technology and agent networks enabled telecom operators to become fintech companies as far back as 2007. Those same telcos now derive a significant amount of their business from the financial services they ushered in. M-Pesa, Kenya’s leading mobile money service provider, now accounts for more than 40% of Safaricom’s (its parent telecom operator) mobile service revenue.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, 55% of the population possesses a financial account, with mobile money’s rise boosting that number in recent years. That’s approximately double the amount of Africans with an internet connection.

Too early to call

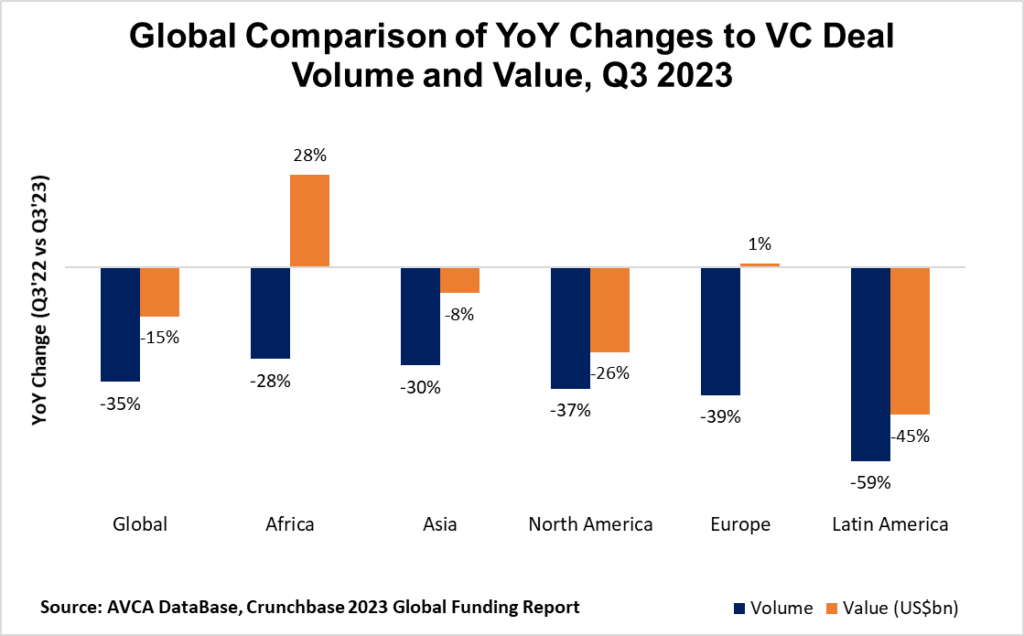

In this context, many are the Cassandras lamenting venture capital’s failure in Africa. These conclusions seem premature, both because the industry itself is novel but also because the digital ecosystem it operates in is still nascent.

Even by removing Africa from the picture, venture capital is a long-term industry, and its illiquidity can lead to prolonged exit times. According to Dealroom, only 17% of portfolio startups globally exit within the investment period of 10 years. Initial, tangible VC investments in Africa debuted around 2012. We believe that the pessimists are neither right nor wrong: they’re just pontificating too early.

That being said, the past decade has drawn the contours of what can be improved and highlighted what has worked.

# years it takes for portfolio startups to exit, along with exit size (Dealroom)

The casino analogy

Casinos constitute another pertinent venture capital analogy. Addiction and money laundering aside, a casino is a fascinating business. In a casino, a few people win exuberant amounts, while the many ‘losers’ subsidize the entire operation. In return for setting up the infrastructure, applying rules, and mediating disputes, the casino pockets a handsome amount of the proceeds as profits.

Venture capital’s logic is similar to a casino’s. “Winners” are the top decile of skilled VC funds reaping outsized returns. “Losers” are the VC funds that don’t return the amount of money they promised their investors (LPs). The casino itself is the government, collecting tax revenue in return for organizing the game.

Without casinos’ power law gains distribution, no one would play. It is by design that ‘returns’ are extremely skewed, enabling the casino economy to work. VC is similar: it is by design that most of the returns come from the top decile funds and companies because winning in venture capital is hard. It wouldn’t be possible without the entire ecosystem structure, and failing companies still provide tremendous value to the other players.

Mixing profitability and venture scale

While far from a solely African problem, the confusion between these two terms may cause damage. In light of hostile, macroeconomic conditions, many Africa-focused VCs have started demanding that their startups reach “profitability” even if this means compromising on hyper-growth.

This is partly a mistake: if investors want to invest in profitable African businesses, they can invest in African banks for example, which exhibit fantastic ROIs. Or switch to private equity. But that isn’t the VC game.

VCs demanding that their portfolio companies, especially young ones (pre-seed and seed stages), become profitable quasi-eliminates any potential “home-run” companies. The latter can only emerge through market share dominance, a process facilitated by operating at a company-level loss when competitors can’t. Those home-run companies are the only way a VC can reach the outsized returns it promised its LPs.

Herein lies the confusion between profitability as a whole and positive unit economics at the marginal level. VCs should be encouraging their portfolio companies to reach “venture scale”. Venture scale is the ability to grow at a decreasing and very efficient marginal cost. This implies tinkering and getting unit economics to a point where the revenue generated from each unit sold is superior to what it costs to make it. This metric is referred to as the “contribution margin”.

A company with a positive contribution margin, which can be unprofitable as a whole because it has very high fixed costs (such as R&D), has a clear path to long-term profitability. This justifies pumping large amounts of money into it, enabling the company to reach the economies of scale it needs to win.

Companies continuing their fundraising route, and even going public, with iffy contribution margins either speed-run their death (Airlift) or make their lives significantly harder (SWVL). Those are the business models VCs should be wary of. However, a blind focus on company-level profitability for the sake of profitability doesn’t make much sense in the VC context. There are very useful data points that companies can follow to see if they are on the right path, such as the “burn multiple” or the “magic number”.

VCs investing in African startups should be cognizant of this difference as they hit the brakes during the current funding winter.

African VC: Expensive and risky, replete with singular challenges

The early innings of the African venture capital ecosystem have made two things clear: venture capital in Africa is expensive and risky.

It is expensive because lagging infrastructure might nudge startups to build out their own, which costs money, additional time, and expertise. If the infrastructure needed can’t be built in-house, such as public infrastructure (roads, etc…), the startup will have to contend with the higher prices resulting from the existing infrastructure’s inefficiencies. This is a salient problem for logistics startups, for example.

Funding high-growth businesses in Africa can thus turn out to be an expensive endeavor, generating infrastructure costs that wouldn’t be necessary in other, more developed markets.

It is riskier if funded by international funds in international currencies (USD, Euros, GB Pounds, etc…). Take Nigeria for example, one of the continent’s venture capital darlings. Earlier last year, the Central Bank of Nigeria floated the local currency (the naira) away from its traditional peg to the USD, in a bid to liberalize the economy. The move led to the naira’s sharp and sudden devaluation, revealing overarching uncertainty about its strength.

This was a disaster for Nigerian startups, especially those that reported their revenue numbers in dollars (a given if foreign investors are on the cap table). The devaluation meant that similar revenue in naira from one month to another could render just half the value in dollars.

If Nigerian startups had converted any USD from their funding rounds into naira, their buying power was also drastically slashed. From the investor’s point of view, the startup’s $USD valuation got trimmed almost overnight, due to factors outside the founders’ control. This also creates currency translation issues, making reporting of actual performance of ventures in local and USD currencies trickier and less reliable.

This is not an issue in developed markets with stronger currencies and free capital flows, such as the US or Europe. It can be reasonably assumed that this issue has contributed to Nigeria’s drop in startup investment.

To sum it all up: African venture capital is expensive because startups have to build out or deal with decrepit infrastructure hence requiring specific business models, and comparatively riskier since valuations are subject to currency-induced volatility.

Fraud in African tech: an optical illusion?

The past year was also punctuated by the downfall of some well-funded African startups, failures attributed to a nebulous mix of founder wrongdoing, financial mismanagement, and outright fraud. As is often the case, very few people will uncover the full story behind these crashes.

Some observers were quick to generalize the trend, using these failures as proxies to gauge the integrity of all other African founders. Shady founders do and will always exist, regardless of the ecosystem’s maturity. There is an argument to be made that the safeguards against those founders are potentially lower in young ecosystems such as Africa, where governance standards have not yet been standardized and where investors are less aware of African markets’ specific features. That is a solvable problem.

These are normal ecosystem growing pains that need to be rationally addressed but are no cause for doomsday rhetoric.

What’s needed: liquidity

Venture capital’s equation is simple: can you invest in startups that will exit, and will those exits return (much) more money than your LPs put in while creating economic value for the clients, suppliers, and all stakeholders?

Exits, meaning a startup getting acquired or going public, are crucial to the venture capital ecosystem’s health. VCs are investing with the intention of outsized exits, but sometimes those turn out to be impossible. Adverse market conditions, a non-scalable business model, founder conflict… Exits can be jeopardized for various reasons.

When such a situation arises, invested VCs will sometimes face the choice of either settling down for a smaller exit or losing their money outright. We believe that the importance of these small exits, such as “acquihires” should not be underestimated as they remain important for VCs required to distribute to their LPs. Typically, they will also provide cash-outs for angel investors, employees, public institutions, and founders. These cash-outs will hopefully convince these stakeholders to pour money back into the ecosystem, launching a virtuous flywheel.

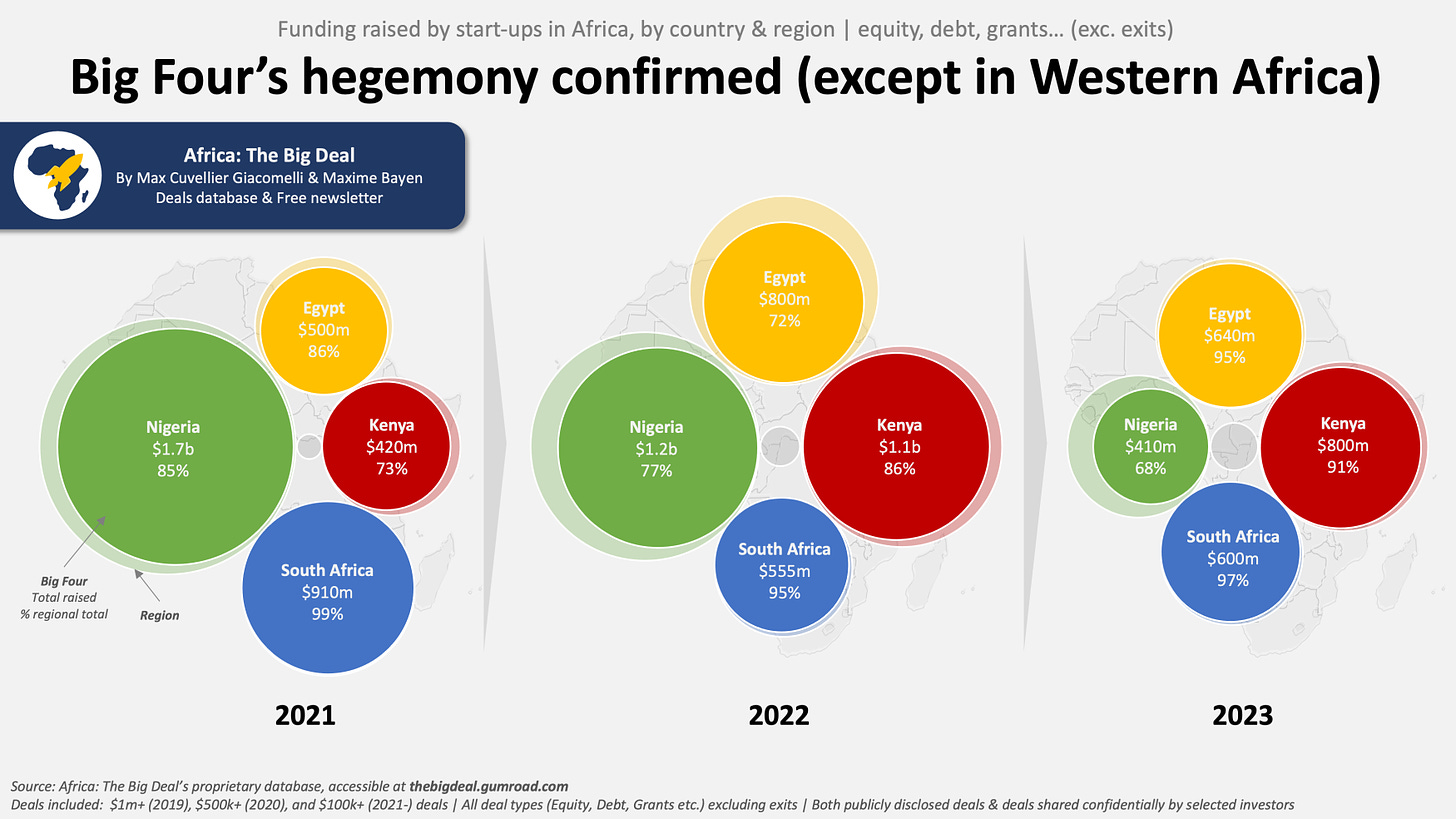

While the number of exits has been increasing on the continent, actual numbers of their combined value are hard to come through (many deals don’t disclose their terms). Briter Bridges also interestingly notes that the countries and sectors receiving the most amount of funding aren’t necessarily the ones with the most lucrative exit paths.

Liquidity events are essential to Africa’s VC market. So far, most of the attention has gone toward fundraising numbers, a relevant proxy for market sentiment but not market viability or growth. More attention should be paid to the African exit market, its intricacies, its possibilities, and its obstacles.

The future of African M&A

An overwhelming majority of exits for African startups today entail a merger/acquisition (M&A).

Two African M&A trends are likely to materialize over the next couple of years.

First is the consolidation of African startups operating in the same sector yet different geographies, and struggling to live up to the valuation they raised. The recent Wasoko-MaxAB merger announcement is an example of such.

Second is the potential rise of “south-south” startup acquisitions. The socio-demographic similarities between emerging markets make the solution built in one place potentially applicable to another, even thousands of miles away. This seems to be truer for lesser regulated sectors, such as edtech or e-commerce, but harder for more supervised ones, like fintech. The recent Orcas-Baims acquisition is an example of such a deal.

Players such as Brazil’s Ebanx, Estonia’s Bolt, and Russia’s Yango Delivery all operate in Africa and represent new competitors (and potential acquirers) for local African startups. This could stimulate the local M&A scene, but more importantly, entice other well-capitalized startups in emerging markets to expand to Africa.

Conclusion

Venture capital in Africa is a recent phenomenon, one whose success can’t yet be pronounced due to the sector’s long-term nature. These early years have highlighted the specificities of African venture capital, some of which aren’t relatable to more developed markets or even other emerging markets. This means copy-pasting Western frameworks in the African context is a faulty and lazy approach.

Foreign and local VCs investing in African startups should seek to deeply understand the continent’s intricacies, and develop fresh strategies to deal with them.

The ecosystem should give itself time. Adopting a longer-term view discounts short-term pessimism and allows one to rationally solve the challenges that arise. African venture capital can be a fantastic locomotive for African growth, but railroads don’t get built overnight.

As the Bambara saying puts it, munyu tè nimisa : one never regrets patience.

This article was written for and exclusively published in the Realistic Optimist, a paid publication making sense of the recently globalized startup scene.

About the Author

Mathias Léopoldie is the co-founder of Julaya, an Ivory Coast-based startup that offers digital payment and lending accounts for African companies of all sizes. Julaya serves over 1,500 companies, processes $400M of transactions, and has raised $10M in funding.

Julaya has offices in Benin, Senegal, France, and Ivory Coast.

Mathias would like to thank Mohamed Diabi (CEO at AFRKN Ventures) and Hannah Subayi Kamuanga (Partner at Launch Africa Ventures) for their thorough advice on this piece.