Par l’équipe Daba – Votre partenaire pour investir en Afrique avec succès

Introduction : Investir en Bourse, un levier pour construire son avenir financier

Investir en Bourse n’est plus réservé à une minorité d’initiés. Aujourd’hui, grâce à des solutions accessibles comme Daba Finance, investir devient une opportunité ouverte à tous, même avec un petit capital.

Mais pourquoi devriez-vous sérieusement envisager d’investir en Bourse, surtout en Afrique, et comment le faire intelligemment ?

Ce guide complet vous donne toutes les réponses pour démarrer, apprendre et prospérer en toute confiance.

Cinq raisons d’investir en bourse

1. Pourquoi investir en Bourse aujourd’hui ?

a) Faire fructifier votre épargne efficacement

Les livrets d’épargne classiques offrent aujourd’hui des rendements faibles, souvent inférieurs à l’inflation. En revanche, investir en Bourse permet de viser une croissance réelle de votre capital sur le long terme.

Historiquement, les marchés boursiers mondiaux affichent des performances annuelles moyennes entre 6 % et 8 %.

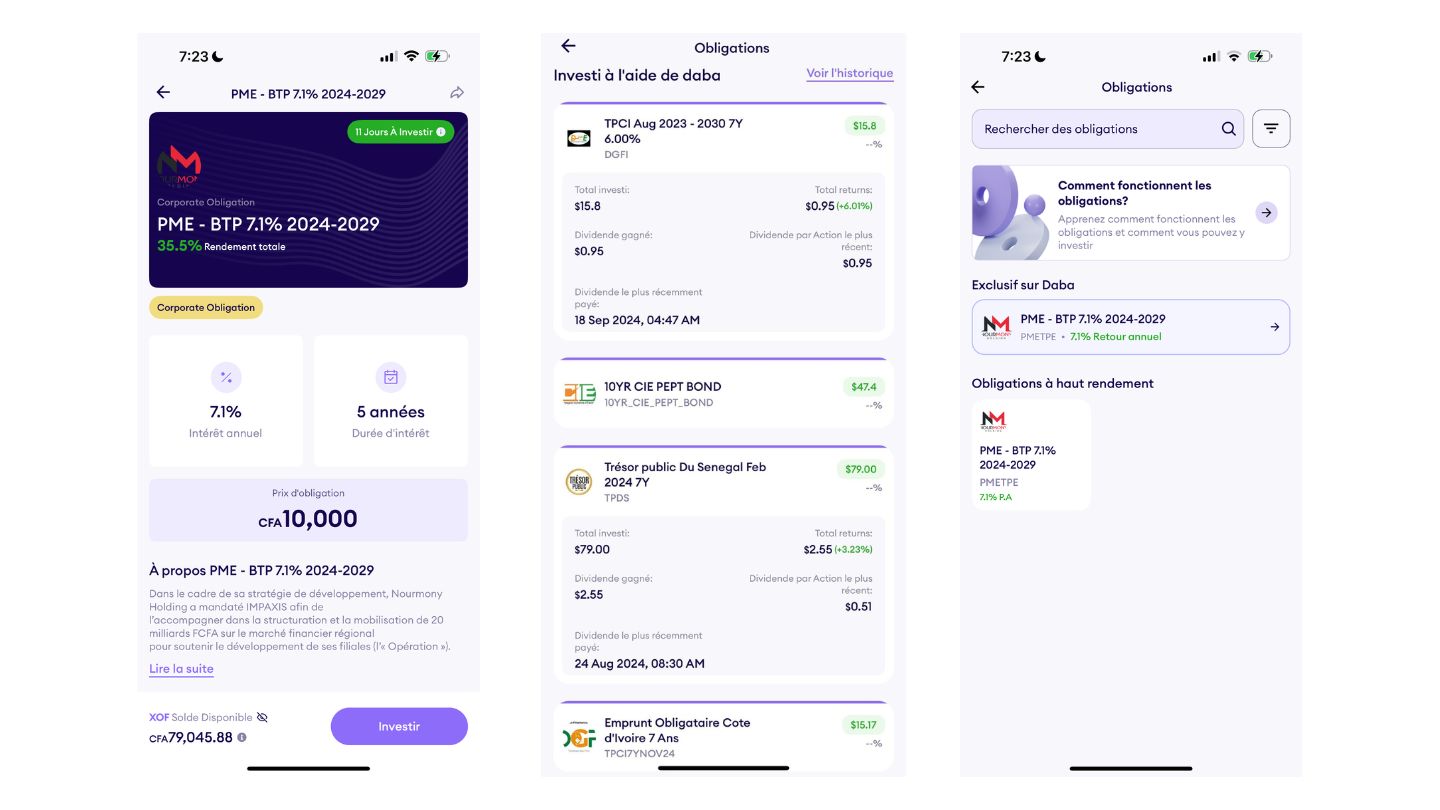

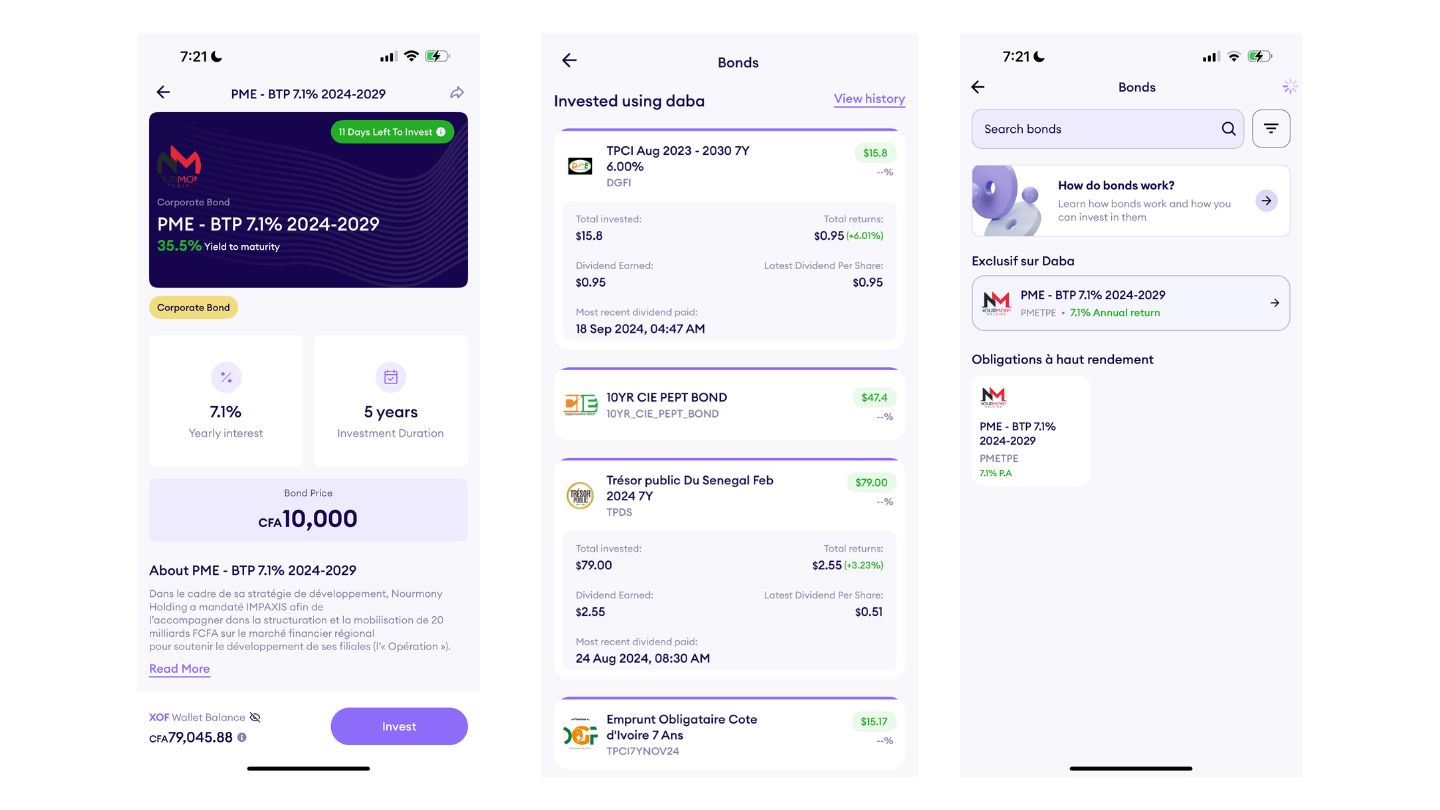

Avec Daba, vous pouvez facilement accéder à la Bourse régionale africaine (BRVM) dès 10 000 FCFA, en quelques clics, via une application sécurisée et intuitive.

b) Diversifier ses placements

La célèbre règle “Ne jamais mettre tous ses œufs dans le même panier” s’applique parfaitement à vos finances.

En combinant épargne de précaution, immobilier, et investissements boursiers, vous réduisez votre risque global. La Bourse offre une diversité d’actifs, de secteurs et de pays, notamment en Afrique de l’Ouest où la dynamique économique est prometteuse.

Sur l’app Daba Finance, vous pouvez diversifier facilement entre actions, obligations, fonds gérés et bientôt, ETFs régionaux.

c) Préparer des projets de vie

Investir en Bourse, c’est aussi préparer :

- Votre retraite

- Les études de vos enfants

- L’achat d’un bien immobilier

- Votre succession

Avec l’Académie du Patrimoine de Daba, vous apprenez à définir vos objectifs financiers et à choisir une stratégie adaptée à votre horizon d’investissement.

2. Investir en Bourse : une démarche accessible à tous

Contrairement aux idées reçues, investir en Bourse est aujourd’hui simple et ouvert à tous.

Que vous soyez étudiant, salarié ou entrepreneur, vous pouvez commencer à construire votre patrimoine progressivement, même avec un petit budget.

Grâce à Daba, l’ouverture d’un compte est 100 % digitale, sans paperasse compliquée. L’application vous guide pas à pas pour réaliser votre premier achat d’actions, obligations, ou fonds communs de placement.

3. Comment bien investir en Bourse ? Les bonnes pratiques

a) Se former avant de se lancer

La connaissance est votre meilleur allié. Avant de placer votre argent, il est essentiel de comprendre :

- Le fonctionnement des marchés financiers

- Les mécanismes des actions et obligations

- Les risques associés

La Daba Academy propose une formation complète sur la Bourse, la BRVM, et l’investissement en Afrique.

24 modules progressifs, accessibles partout, vous permettent d’acquérir une véritable expertise pour investir sereinement.

🎓 Plus de 30 000 apprenants formés grâce à nos webinaires gratuits et cours en ligne.

b) Diversifier son portefeuille

Investir tout son argent sur une seule action est risqué. Il est recommandé :

- De répartir vos investissements sur plusieurs secteurs (banques, télécommunications, agro-industrie…)

- De varier entre actions et obligations

- De panacher entre entreprises de tailles différentes

Sur Daba, des “collections thématiques” vous sont proposées pour diversifier simplement votre portefeuille.

c) Investir régulièrement

Plutôt que d’essayer de “timer” le marché (acheter au plus bas et vendre au plus haut), il est souvent préférable d’investir de façon régulière (par exemple tous les mois).

Cette approche appelée “investissement programmé” réduit le risque lié aux fluctuations à court terme.

Bientôt sur Daba, vous pourrez automatiser vos dépôts et achats d’actifs pour construire votre portefeuille en toute tranquillité.

d) Connaître et accepter le risque

La Bourse présente une volatilité naturelle. Les cours montent… et descendent parfois.

L’essentiel est de rester investi sur le long terme et de garder en tête vos objectifs.

Le premier principe : n’investissez que l’argent que vous êtes prêt à immobiliser pendant plusieurs années, et que vous n’aurez pas besoin à court terme.

Avec l’Académie du Patrimoine, nous vous enseignons également à évaluer votre profil de risque et à adapter votre stratégie d’investissement en conséquence.

4. Pourquoi choisir Daba pour investir en Bourse ?

Daba n’est pas juste une application : c’est votre écosystème complet d’investissement en Afrique :

- Ouverture de compte simplifiée en 5 minutes

- Investissement accessible dès 10 000 FCFA

- Sélection d’actions recommandées par des experts via Daba Pro

- Accès à des fonds gérés, parfaits pour ceux qui préfèrent confier leur portefeuille

- Formations intégrées avec l’Académie du Patrimoine

- Actualités boursières en temps réel pour prendre de meilleures décisions

🌟 Daba, c’est déjà plus de 30 000 utilisateurs qui bâtissent leur avenir financier en Afrique.

5. Témoignages : Ils ont franchi le pas

« Avec Daba, j’ai pu acheter mes premières actions sur la BRVM en moins de 24h, et suivre l’évolution en direct. La formation de l’Académie m’a beaucoup aidé à comprendre comment choisir les bonnes entreprises. »

— Sarah, jeune investisseuse basée à Dakar

« L’interface est intuitive, les formations sont complètes, et surtout, j’ai l’impression de contribuer au développement économique de ma région. »

— Kofi, entrepreneur à Abidjan

Passez à l’action aujourd’hui

Pourquoi investir en Bourse ? Parce que c’est l’un des meilleurs moyens de faire croître votre épargne, de financer vos projets, et de participer au dynamisme économique de l’Afrique.

Avec Daba Finance et l’Académie du Patrimoine, vous avez tout ce qu’il vous faut pour réussir :

➡️ Formation pratique

➡️ Application intuitive

➡️ Investissements accessibles

Ne laissez pas votre argent dormir. Faites-le travailler pour vous dès aujourd’hui.

📲 Téléchargez Daba Finance maintenant

Commencez à investir dès 10 000 FCFA et bâtissez votre patrimoine.

🔗 Télécharger l’application Daba

🎓 Découvrez la Daba Academy et formez-vous à l’investissement :

🔗 Rejoindre l’Académie du Patrimoine