Contributed by Ajibola Awojobi, founder of BorderPal.co by ErrandPay.

Flashy new tech companies and cutting-edge tech get a lot of buzz. But for investors, the real excitement lies in booming tech hubs, areas where new companies are constantly popping up, fueled by money from around the world. These up-and-coming hubs offer a chance for quick profits compared to the crowded tech industries in more advanced markets.

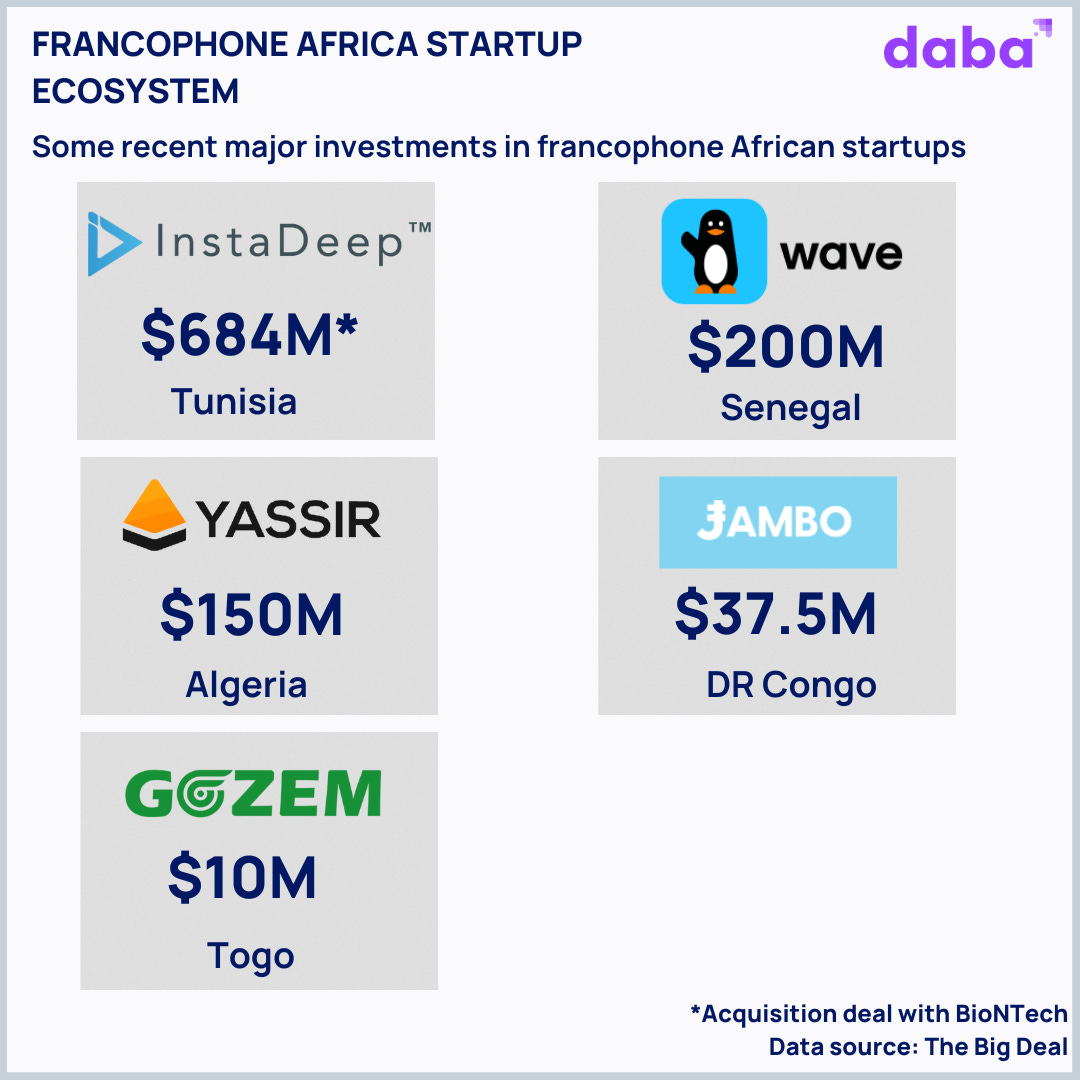

That has been the tale of fintech in Africa over the past few years. Many in the global investment community have looked at the continent as the “future” or “next frontier” of financial technology, with investments flooding into the sector at an unprecedented rate.

From 2016 to 2022, funding for African startups grew 18.5x, 45% of which was attributable to fintech, per a McKinsey report. In the eight years to 2023, nearly $4 billion in equity funding was poured into fintech startups, while the sector accounted for around half of the total financing raised last year.

The surge in funding is partly behind the boom in Africa’s fintech, propelling it to rank as one of the fastest-growing in the world. But the concentration of investor capital on a select few players (in 2023, 75% of all equity funding secured by African fintech startups went to just ten companies) has inadvertently made the sector a “land of giants” of some sort. This top-heavy ecosystem may overlook a vast untapped potential.

A handful of well-known names dominate fintech headlines and funding. Companies like Flutterwave, Chipper Cash, MNT Halan, TymeBank, Wave, Jumo, and OPay have become household names, nearly all valued at over $1 billion. While their success is commendable, this concentration of resources raises a crucial question about the broader impact on financial inclusion across the continent. It limits innovation and creates a narrow funnel for financial services distribution, potentially leaving millions underserved.

Despite the growth of fintech, financial exclusion remains a significant challenge in Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa’s banked population jumped from only 23% in 2011, but most Africans still do not have bank accounts.

Around 360 million adults in the region do not have access to any form of account—roughly 17% of the global unbanked population, per World Bank estimates. This vast number represents not just a challenge but an enormous opportunity for a different kind of financial innovation and venture building.

“Undiscovered Founders”

Traditional financial institutions and even fintech startups have struggled to reach these populations due to various factors, including low urbanization rates, infrastructure limitations, high operational costs, and a lack of tailored products. This is where the power of undiscovered founders lies.

These religious leaders, community leaders, and small business owners have established trust, credibility, and deep connections within their local communities. Still, they may lack the technical expertise or capital to launch fintech ventures. They understand their neighbors’ financial needs and challenges, acting as bridges between the formal and informal economic sectors.

The power of these untapped networks cannot be overstated. In many African communities, trust is currency, and these leaders have spent years building social capital. For instance, a pastor in a rural Nigerian village might have more influence over financial decisions in their community than any glossy marketing campaign from a Lagos-based fintech company.

While these potential founders hold immense potential through their network and trust, they face significant challenges in leveraging these to provide tech-driven financial services.

Access to capital is a major obstacle. Banks view them as high-risk borrowers, while traditional venture capital rarely reaches these individuals, making it difficult to secure funding for starting or expanding financial service offerings. In addition, many lack the technical skills to build and maintain fintech platforms, while navigating the complex world of financial regulations can be daunting.

Here’s where the concept of white labeling emerges as a game-changer. Put simply, white labeling is the practice of one company making a product or service that other companies rebrand and sell as their own. This model could be adapted to empower undiscovered founders by providing them with ready-made, compliant fintech solutions (technological infrastructure and core services) that they can brand and distribute within their networks.

Imagine a community leader partnering with a fintech company to offer their congregation or local businesses branded mobile wallets or microloans. The established company handles the complex back-end technology and regulatory compliance, while the community leader leverages their trusted network for customer acquisition.

This approach solves several problems simultaneously: undiscovered founders get affordable access to advanced technology, existing trust networks are leveraged for customer acquisition, and regulatory compliance is ensured through the central platform. It also offers a distinct advantage over traditional funding models. Empowering multiple “mini-startups” across the continent through this model could prove more cost-effective than pouring resources into a single large-scale venture.

The analogy of Coca-Cola’s distribution system comes to mind. Its success in reaching even the most remote parts of Africa is attributed to its micro-distribution centers (MDCs) in Africa — small hubs that distribute beverages to small retailers.

Over 3,000 are usually run by individuals who live in the community; they employ local people and handle the last-mile distribution. They create around 20,000 jobs and generate millions of dollars in annual revenue. Similarly, empowering undiscovered founders creates a capillary network of financial service providers, reaching the farthest corners of the continent.

Consider the cost-effectiveness: Imagine funding 100 local leaders, each reaching 1,000 individuals, compared to funding one large fintech startup aiming to reach 100,000. The white-labeling model fosters a more cost-efficient and geographically expansive approach to financial inclusion. Instead of one company trying to penetrate diverse markets, hundreds or thousands of local leaders could adapt services to their specific communities.

Beyond financial inclusion

Increasing account ownership and usage could increase GDP by up to 14% in economies like Nigeria. By leveraging undiscovered founders, we could accelerate this growth while ensuring it’s more evenly distributed. However, the implications of this model extend far beyond just increasing access to bank accounts or broad financial services.

Empowering local leaders as fintech distributors could increase job creation, as each mini-startup creates multiple jobs within its community. Profits from financial services would stay within local communities, and local founders would be best positioned to understand and meet their communities’ specific needs, thereby creating more tailored products.

As trusted figures introduce these services, they could play the crucial role of financial educators, dispelling myths and building trust around formal financial services. Financial literacy is essential for making informed financial decisions and avoiding predatory lending practices. Undiscovered founders can bridge the knowledge gap, fostering a financially responsible citizenry.

While promising, this model is challenging. Ensuring quality control across numerous mini-startups, managing regulatory compliance, and preventing fraud are all significant considerations. There’s also the question of identifying and vetting potential undiscovered founders, but these challenges are manageable. With proper systems in place, including rigorous vetting processes, ongoing training, and robust monitoring systems, these risks can be mitigated.

The concept of undiscovered founders represents a paradigm shift in our thinking about fintech distribution in Africa. We can create a more inclusive, resilient, and far-reaching financial ecosystem by leveraging existing trust networks and empowering local leaders.

This approach aligns with the African proverb, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” While the current model of concentrated investment may lead to rapid growth for a few companies, empowering undiscovered founders could take us much further in achieving true financial inclusion.

As we look to the future of fintech in Africa, it’s time to broaden our perspective. The next big innovation in financial inclusion might not come from a tech hub in Nairobi or Lagos but from a small shop owner in rural Tanzania or a community leader in suburban Ghana. By providing these undiscovered founders with the tools they need, we can unlock a new wave of innovation and inclusion, bringing financial services to millions who traditional models have left behind.

The potential is enormous for financial returns and social impact, economic empowerment, and the realization of Africa’s full potential in the global digital economy. It’s time to discover the undiscovered and rewrite the story of fintech in Africa.